Soul Food

Sudan

October 2019

As a photographer, I’ve always believed that the most important skill lies not in the technical, but rather in the ability to connect. A portrait can be styled, lit and retouched to perfection, yet leave you cold, whereas a photograph can be blurred and dimly lit, but for a moment lets you see into the soul of another. Maybe I’m overromanticising, but for me taking a portrait is one of the most intimate moments I can share with another.

My work as a humanitarian photographer takes me to war zones, refugee camps and some of the most uninhabitable places on Earth. How can you build relationships in these places of crisis where families are going through incredible hardship? Over time I’ve found the answer to be in food and in the intimacy of cooking and eating together. A shared meal is where we go from stranger to acquaintance to friend.

When the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) asked me to document the experiences of refugees and the internally displaced people of South Sudan, I knew that I wanted to tell those stories through food. I’ve been visiting the country for 15 years, yet despite my passion for learning about a nation’s cuisine, I felt I knew little of the culinary culture there.

South Sudan is the world’s youngest nation. It’s also a country shattered into pieces by years of war and ethnic violence. It has one of the lowest life expectancies and highest child mortality rates in the world, and is plagued by famine and drought. Nearly seven million of its inhabitants face food insecurity.

To dismiss food simply as a necessity is to dismiss the way it’s bound up with a culture’s identity. While a family may struggle to gather enough food to survive, it will still be cooked with love and a nod to tradition, and savoured with conversation and laughter. In all of the countries I’ve worked in, it’s preparing food and sharing a meal that often gives momentary respite from the realities of war. As Sihan, a Syrian mother relocated to France, said to me: “It’s memories of food at home that will stay with me the longest – and at least I can bring those flavours with me.”

On the edge of Juba, South Sudan’s capital, lies the Mahad Camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs). Several thousand South Sudanese have found refuge here from the country’s brutal civil war and tribal conflict, but life in the camp is hard. It’s existence at its most basic. Families live crammed together under shelters made of plastic sheets. Education is limited and there is no space to grow food, meaning that IDPs are dependent on food handouts. I spent a week here listening, cooking and learning the stories behind a few families’ most meaningful meals.

The UNHCR works to safeguard the rights and wellbeing of people who have been forced to flee the fighting in South Sudan. To find out more about their work, visit unhcr.org

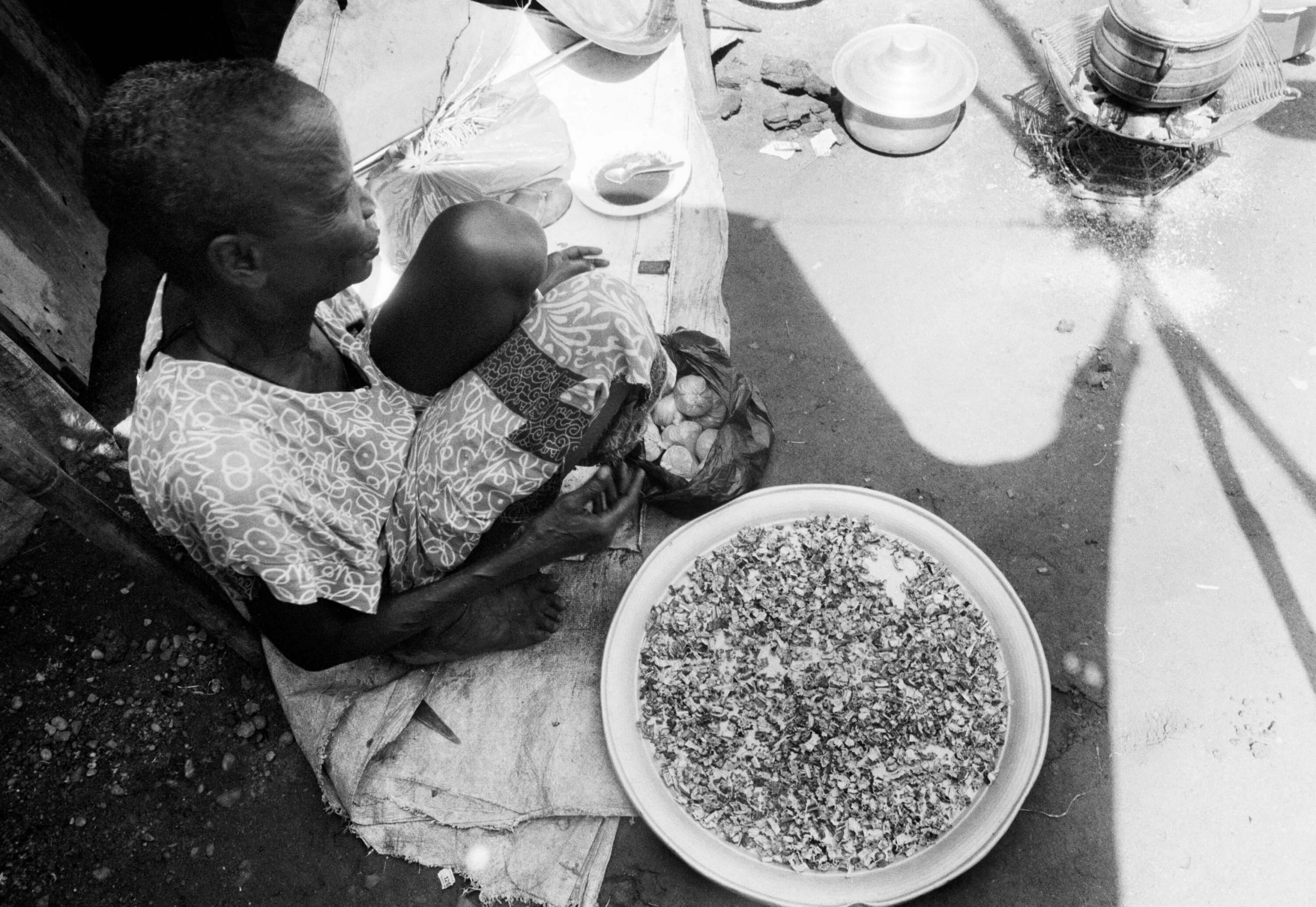

Margaret Mac, 55, fled her home near the town of Bor after her brother and family were killed in 2014. She found shelter in Mahad, but finds it hard not being able to grow her own food. “If you don’t have food you grow, you lose your dignity,” she explains. “Food is my identity. You can tell what you eat by your skin, the way you think, your body; it defines you.”

Despite the challenges, Margaret has found ways to eke out an extra income through her cooking. She dries okra in the sun, then grinds them into a powder which she sells in small packets. When added to stews this okra powder (known as waka or tabiek) thickens and flavours the sauce.

However, it’s in the cooking of her greens that I discover the most interesting story. As Margaret boils deep-green kudura leaves bought from the market, she adds some grey, cloudy liquid from a small bottle. When I ask what it is, she replies: “ash water.”

She goes on to explain how she takes ash from the fire and adds water to make a grey mud, which is then placed in a mug with a small hole in the bottom. Whatever drips from the mug is collected into a bottle: ash water. When added to the tough greens, the acidic liquid helps to soften them and stop them turning yellow. When I ask her who taught her this, she explains that she always just knew.

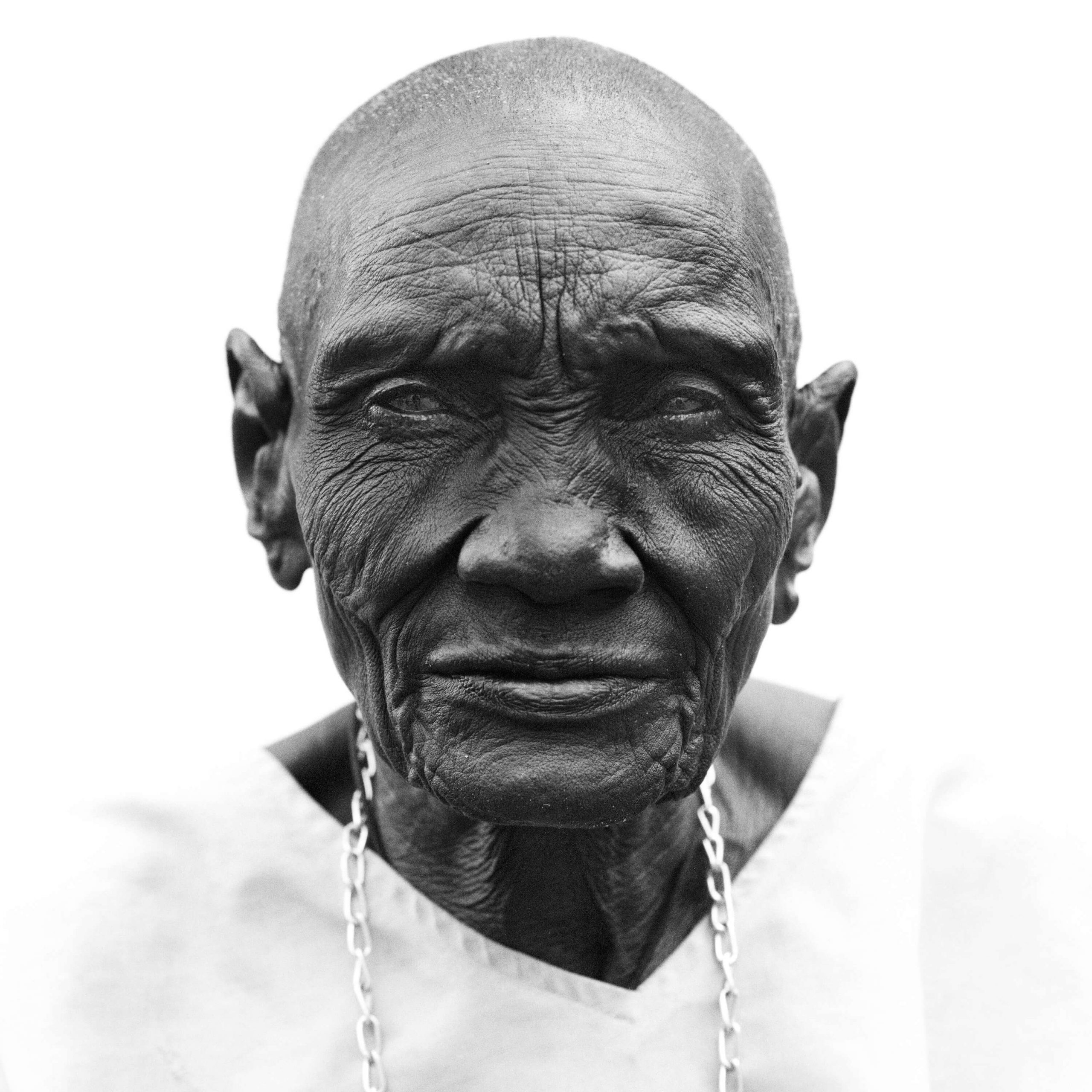

“This is what I would cook for my husband the night before his wrestling contests. He would always win; it gives you the strength of many men. Maybe by tomorrow after you have eaten this, you will have made children!” With this, Deborah Nyuon bursts into laughter.

She stopped counting her age many years ago, but judging from that of her children and her 22 grandchildren, Deborah must be nearly 80. No matter the years, she has an incredible energy and wicked sense of humour.

She’s teaching me to cook welwel (a type of couscous) with the juice of stewed lalob, a date-like fruit. While she may be cracking jokes and laughing, for Deborah food brings back many hard memories of home. Originally from the native Dinka tribe, she misses the traditional life of farming and keeping cattle. War brought death and destruction to her village and she cries as she recounts war-made famines during which she and her family would often go three days at a time without food.

What does she miss most about home? Milk. “I miss the taste of home. When I see people carrying milk I think of home. That is why we are crying, to get back to our cows. If I have milk, I know we also have peace.” Deborah has been living in the IDP camp for five years and, with no sign of the violence in the country stopping, it is unlikely she will be returning home any time soon.

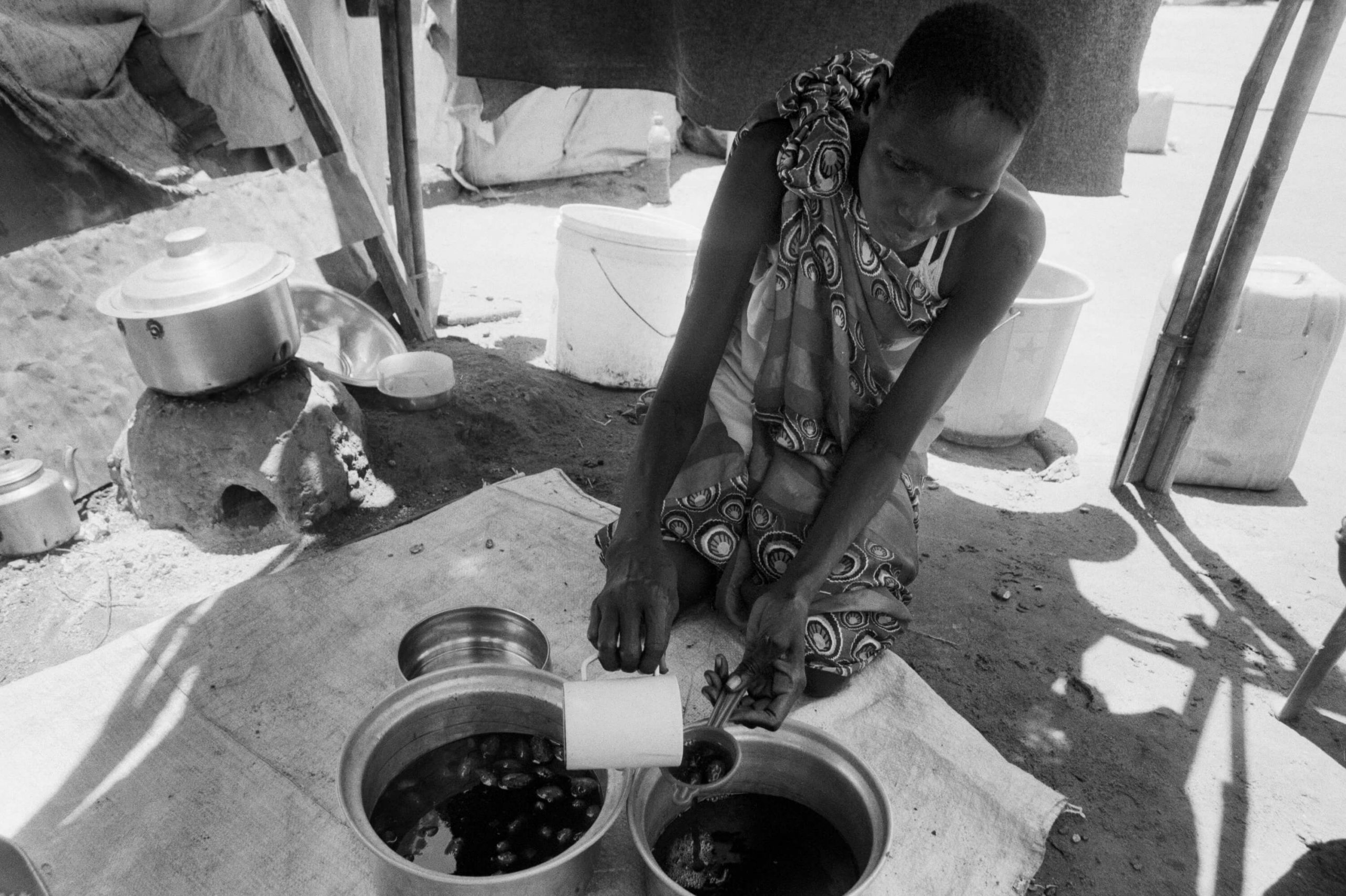

As Amer Anyieth, 42, talks to me about the war and life before she fled her home, her niece Achol, 14, prepares kisra, a thin bread made from fermented sorghum flour. Watching the preparation is hypnotic – she rhythmically pours a little ajin (batter) on a hot plate, scrapes it evenly across the surface, waits a moment, then peels off the wafer-thin, crêpe-like bread. She tells me this staple is the one food that unites South Sudan with Sudan.

However, it’s a different dish that Amer is teaching me this afternoon: a humble tomato salad made with a groundnut sauce. Groundnuts are similar to peanuts, and this sauce made from the nuts’ paste and oil is unique to South Sudan. It’s hard to explain how something so simple in terms of ingredients can be so unique and refreshing in flavour.

For Amer, cooking is far more than just survival. Both her and Achol were displaced from Bor in 2013 and arrived at the Mahad Camp in February 2014. “Giving yourself time to cook is important, it means you cook with joy – and when you cook with joy, it gives you pride because others can feel it when they eat,” she explains to me. “Food is not just for the stomach; it is also for how you feel.”

OTHER STORIES