Iraq: An Open Wound

Erbil

March 2017

Few stories have affected me as much as documenting injured civilians from Mosul. A trip in March 2017 that left bereft of hope, and questioning the validity of the work I do. For a month after returning, I didn’t feel like speaking to anyone, just hid from the world. When faced with such darkness and violence, what value can a photograph have? Does it become just voyeuristic to capture and share those moments? Against such horror a camera seems impotent, its use almost perverse.

_________________________________

I believe photography comes with great responsibility, as soon as I lift my camera to record somebody’s story; I have to ask myself ‘why am I doing this?’ Especially when that work is documenting another’s suffering, nothing in photography goes more against human nature; the process of pointing your camera at somebody injured, afraid or in real peril. So why do it? Does it make a difference?

In March of this year I was based in a hospital run by EMERGENCY in Erbil. Everyday they were receiving dozens of badly injured civilians from the fighting for Mosul. After over a decade of photographing the effects of conflict, the scenes I witnessed there were amongst the worst I’d seen. Babies with amputated limbs, whole families lost, a young child paralysed by a sniper’s bullet. It was beyond words.

In the past I have referred to how I always try and find a positive in such situations, a moment of humour or to show the love between loved ones. But what I witnessed from Mosul left me beyond that, there are times you can find no such image. I think of Raghad, for four days I watch him silently sat by his son’s bed. He nods when I walk by, nothing more. Then one day he comes over and grabs my arm.

“It was not my fault,” he pleads through dead eyes, a hollowed expression I have rarely seen, “I did what I though I was right.”

He goes on to tell me his story. How his family sheltered beneath a table in their home as bombs landed around them. The house opposite was hit, then the house next door, at that moment his nerve gave and he’d told his family they must run. As they left the front door, a third bomb smashed into them. Firas’s wife, three daughters, two sons; all killed instantly. A son, Abdulah, left blind in one eye.

There is nothing one can say to such a story, you cannot say ‘things will get better’, for they never will. There is no hope or positive angle. This is the real face of war and its sinking, sucking horror.

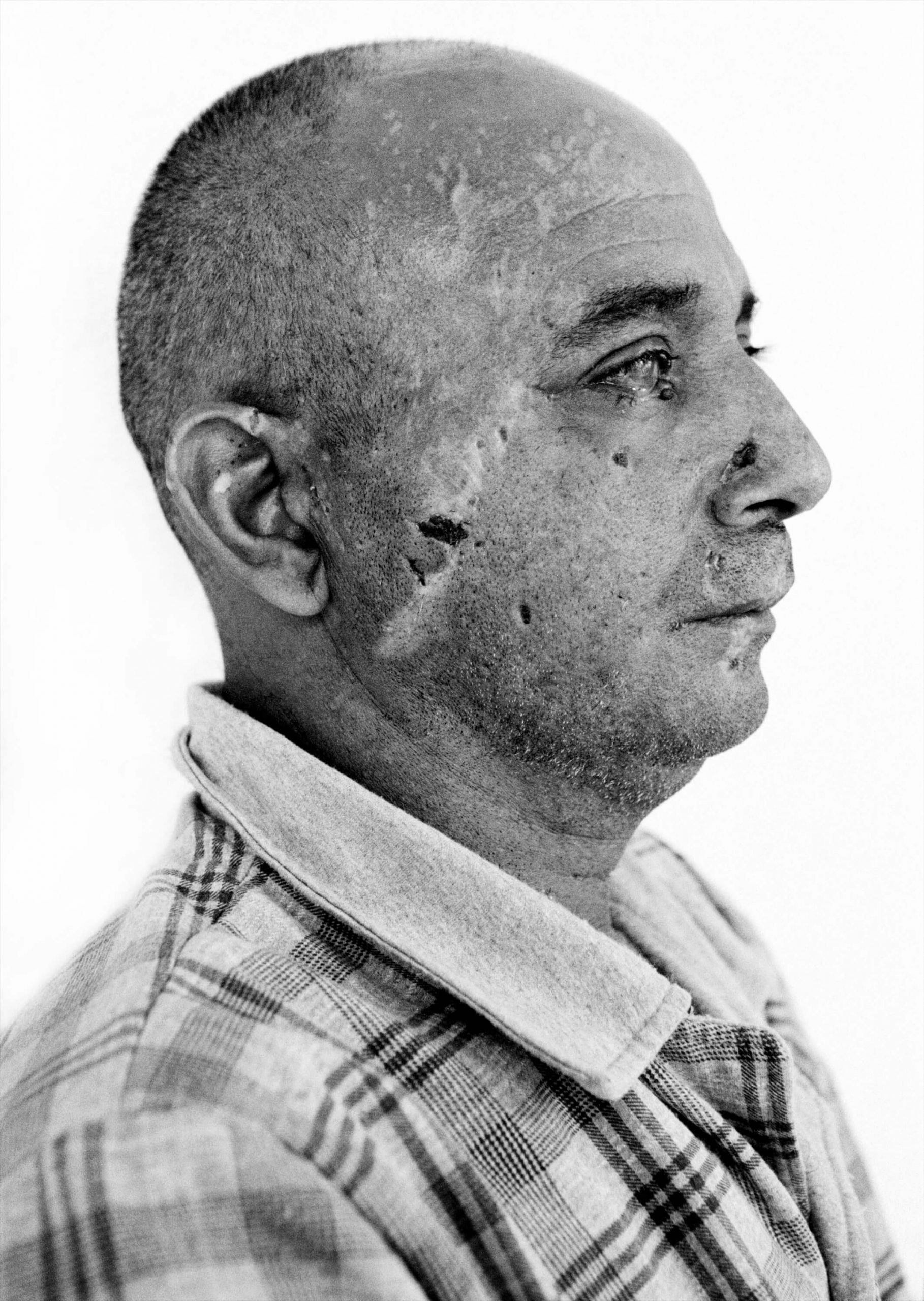

I photograph his son against a white wall, a patch still on his eye. Skin pitted by shrapnel, his expression as hollow as his father’s.

I could only see the darkness and horror of what was happening. I was shooting angry, taking away my normal working practice of not showing the blood and gore. I wanted the world to see what was happening and to reel away as I had.

As the days passed, I knew this was wrong. It was not about me, it was about those I was photographing and to do their stories justice I had to work in a balanced way. I don’t like the phrase to give people voice, they have voices, my job is to make sure those voices are heard.

But still that question, why do it? What difference will a photograph make anyway? Only recently I’d heard my inspiration, the war photographer Don McCullin say there was no point in his years of work – because wars still go on. So if my photograph makes no difference, why point my camera at a child who’s just been injured? It’s an intrusive act and one that must have a purpose.

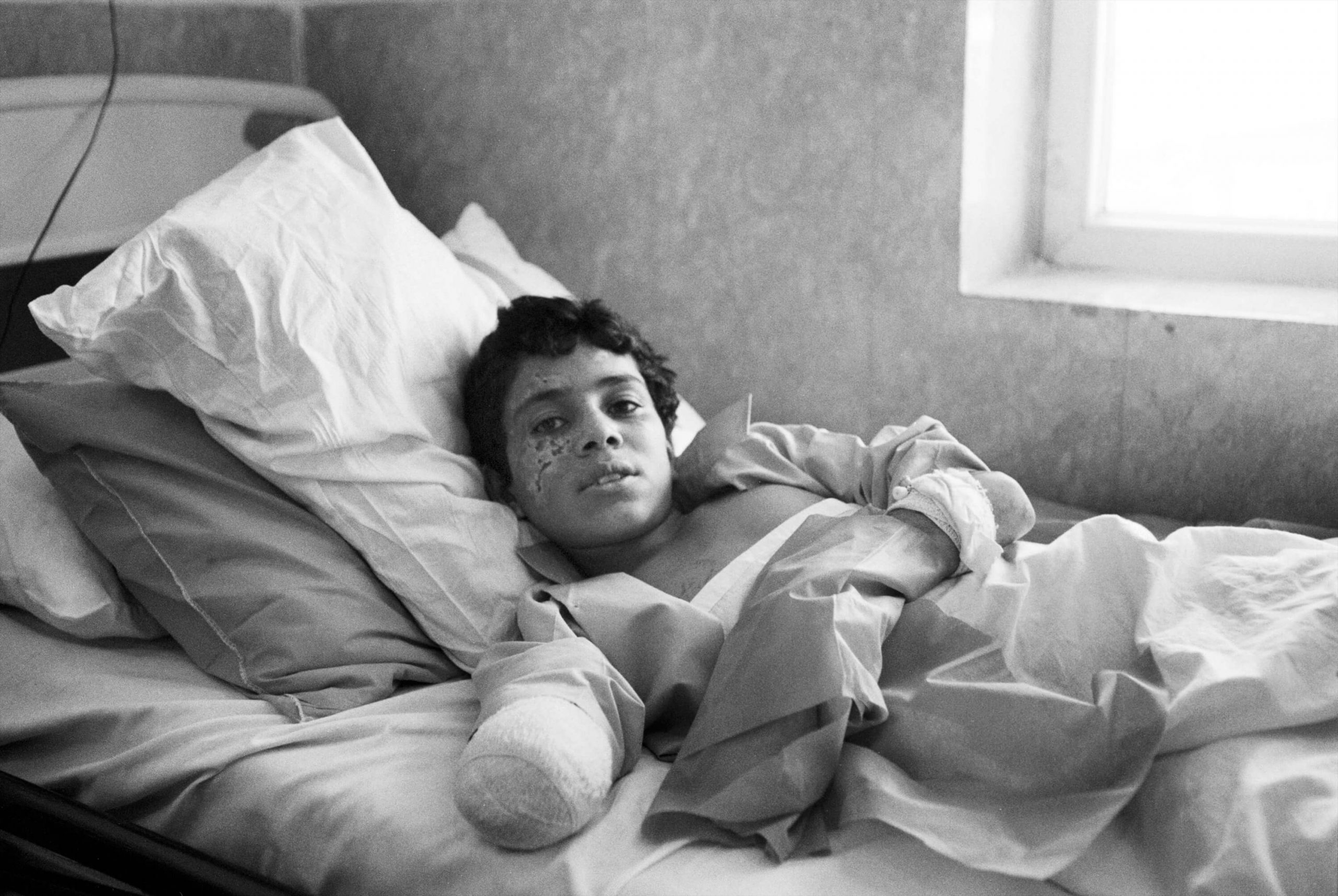

On the last day I’m there I am sat with Dawood Salim, a 12-year-old boy who had lost both of his legs and most of his right hand. For the past week I’ve been visiting him and his mother, he always smiles and jokes. For the first time I feel ready to take his photograph.

I ask his mother, “do you mind if I photograph you son?”

She looks at me, with a defiant yet resigned stare, “When a child is injured like this, the whole world should see.”

Faded photographs of previous patients on the wall of EMERGENCY’s Rehabilitation Centre in Sulaimaniya. Open since 1998, the photographs are a reminder of Iraq’s cycle of conflicts and instability

– Sulaimaniya. March 2017

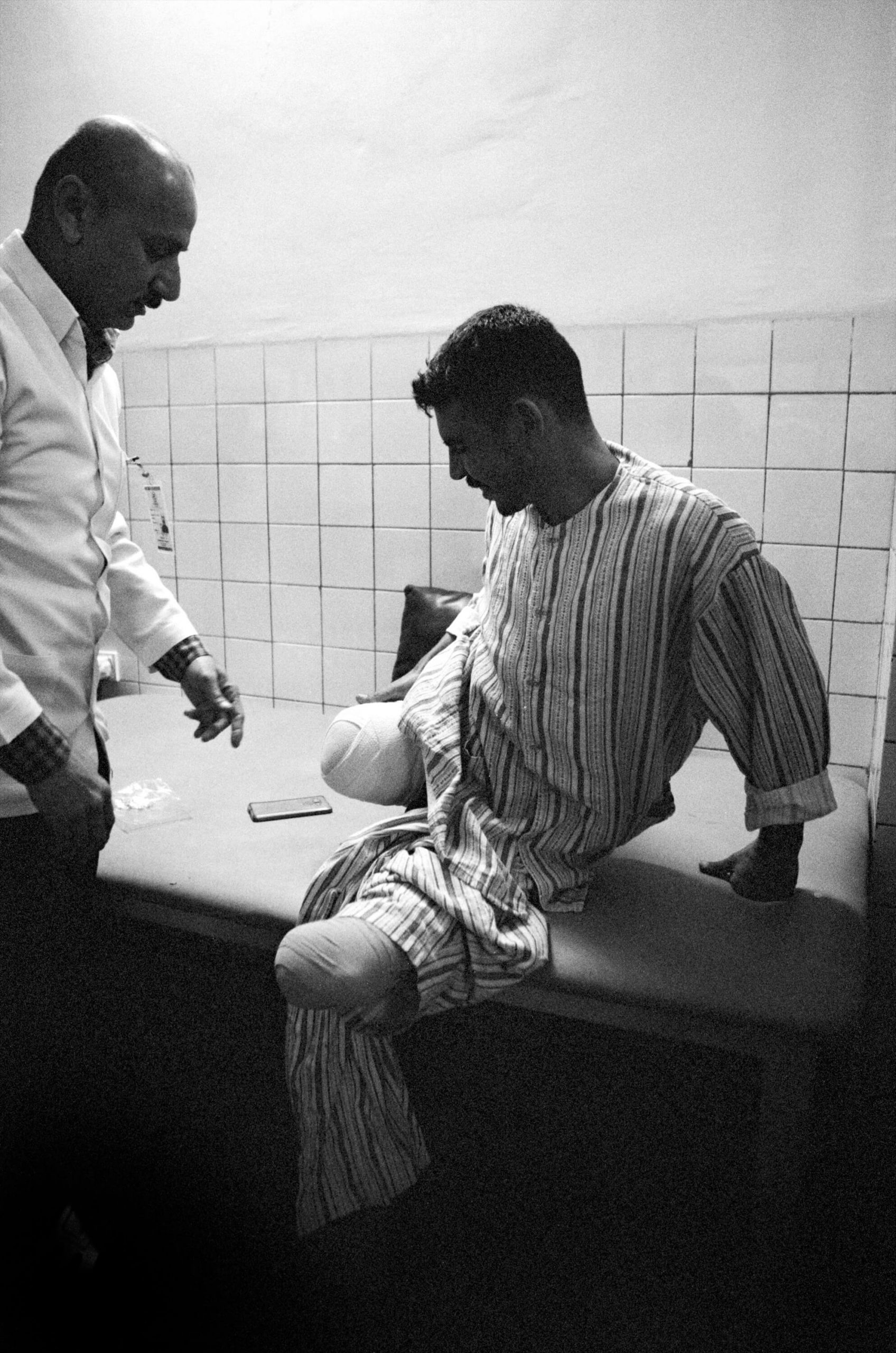

Qutaiba Ahmed, 33, lost a leg after a shell hit his house during the Second Gulf War. Due to a change in the size of his stump, his prosthesis no long fits and so is being assessed for a new leg at EMERGENCY’s Rehabilitation Centre

– Sulaimaniya. March 2017

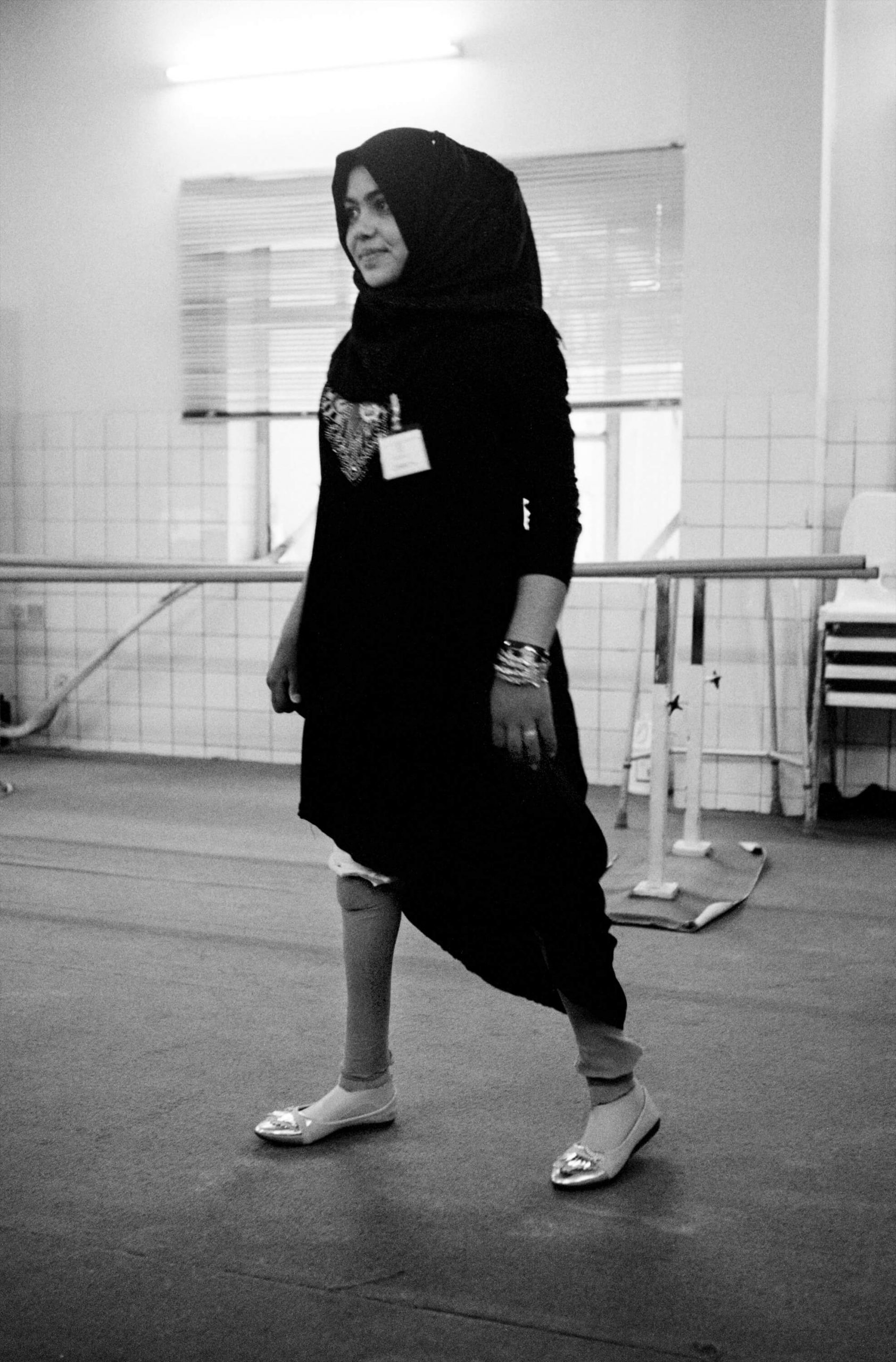

In 2003 Baraq Qahtan Dharee’s parents stepped on a landmine in Kirkuk, as her father was carrying her. Both parent’s died and Baraq lost both legs. Now 16 she regularly has to visit EMERGENCY’s Rehabilitation Centre for new prosthesis. One of the challenges for children growing with limb loss is the constant need to refit the socket as the child grows

– Sulaimaniya. March 2017

Omer Hussan Ahmed, 62, who was injured by a landmine in 1996 tests out a refitted prosthetic leg for fit at EMERGENCY’s Rehabilitation Centre in Sulaimaniya. He has a job in the laundry there.

– Sulaimaniya. March 2017

Mothers and children wait for appointments at the EMERGENCY’s Healthcare Clinic in Ashti IDP camp

– Sulaymaniyah. March 2017

Afrah, 2 years old, is weighed and measured at the EMERGENCY’s Healthcare Clinic in Ashti IDP camp

– Sulaymaniyah, March 2017

Rahaf, 6 years old, is weighed and measured at the EMERGENCY’s Healthcare Clinic in Ashti IDP camp

– Sulaymaniyah. March 2017

Raghad, I month old, has her vital signs monitored at the EMERGENCY’s Healthcare Clinic in Ashti IDP camp

– Sulaymaniyah. March 2017

A child has his vital signs monitored at the EMERGENCY’s Healthcare Clinic in Ashti IDP camp

– Sulaymaniyah. March 2017

Elyas, one month old, at old, is treated at EMERGENCY’s Healthcare Clinic in Ashti IDP camp

– Sulaymaniyah. March 2017

A child has his vital signs monitored at the EMERGENCY’s Healthcare Clinic in Ashti IDP camp

– Sulaymaniyah. March 2017

A sniper shot Mustafa Mahmoud, 17, as he tried to escape the fighting in Mosul. A life long Real Madrid fan, ISIS had made him cut the team’s badge from his football shirts as they said they were ‘infidel badges’. Despite their warnings, he’s still found ways to watch games, a crime others were killed for during ISIS’s two years in control.

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

Yacub Ahmad, 43, was left blind in one eye and lost his left hand following a blast outside his home in Mosul. “Life will never be as it was. Not for me, not for the city.”

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

Mohamed Nawaf, 14, lost both legs and suffered facial injuries and hand injuries when his friend, who was walking in front of him, stepped on a landmine.

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

EMERGENCY staff clean the wound on Mohamed Nawaf’s head.

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital in Erbil – March 2017

Ahmad Munhal has the dressing on his leg changed. A mortar had injured him as he tried to flee Mosul.

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

Gathban Mahmood, 22, was about to graduate high school when ISIS took control of Mosul. When Iraqi forces liberated his neighbourhood, the schools reopened. After over two years waiting, Gathban was finally able to finish his schooling.

His mother, Amira, described how she bought him some new clothes and watched proudly as he left out of their backdoor to go to his graduation. As the door shut there was an explosion outside. She rushed out to see an ISIS drone had dropped a bomb, and her son was lying in their courtyard, he’d lost both legs.

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

Gathban Mahmood, 22, has a cannula inserted to help manage his pain. He lost both legs when an ISIS drone dropped a converted mortar shell.

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

Nazar Mahmud Ibrahim, 52, is the self-proclaimed ‘luckiest man in Mosul.’ On the day his home in Mosul was liberated from ISIS, a mortar shell landed in his garden. A piece of shrapnel hit his chest, but his keys and wallet saved him, leaving him with an injury just to his shoulder.

“There was 5000 dinar in my wallet,” he explained, “the shrapnel destroyed it, shredded it!”

Worried he may have broken his ribs he rushed to a local medical centre, but was incensed when they said it was cost 1000 dinar for the x-ray.

“I don’t care” he told them, “I have 5000 in my wallet, take it all, just do the x-ray.”

They did, and when he left he kept his word and handed them his wallet with the destroyed 5000 dinar inside it.

“That,” he explained, “is why I’m the luckiest man in Mosul”

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

Abbas Fadil, 8, sits in the gardens of EMERGENCY’s hospital, looked after by his grandmother. His parents were also injured, but were treated in a different hospital.

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

Ahad Abdulah, 10 years, suffered facial injuries when a bomb landed near him, as he and his family fled their home in Mosul. His mother, three sisters and two brothers were killed. His father, Firas, was uninjured.

“I reached a point where I feel nothing anymore,” Firas told me, “Really I would rather die.”

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

Firas Abdulah tends to his son’s dressing. Ahad Abdullah, 10 years, suffered facial injuries when a bomb landed near him, as he and his family fled their home in Mosul.

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

An injured child, who lost a leg in during the fighting in Mosul, waits for further surgery at EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital in Erbil.

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

“This fly is worse that Daesh (ISIS)” jokes Dawood Salim as he tries to brush a persistent fly away from his face with his heavily bandaged hand.

On the 8th of March 2017 Darwood, aged 12, had been tending sheep just outside Mosul when he stepped on a landmine. He lost both legs and his right hand.

“I didn’t know how brave he was,” his mother Nidal told me, “until this. They told me after the explosion he kept trying to stand, even though his legs were so injured.”

By the time she got there, they had loaded him on to a tractor to get him to the nearest hospital.

“He was telling me not to cry. The more you cry, he said, the more I hurt”

What made Darwood’s injury more tragic was it came just days after his family had been freed from ISIS control. For over two years the family had lived in constant fear as they had sheltered Dawood’s uncle who was wanted by ISIS

“They took a friend’s father and decapitated him in front of his family. Just to send a message,” recalled Nidal. “This is who they are.”

They knew if his uncle had been discovered, this would have been his fate, and possible the whole families. ISIS bribed children to inform, and so Dawood had been to scared to have anybody visit.

Looking at her son, Nidal told me “he could tell you a book of stories.”

A few days later, I asked her is she minded me photographing her son, calmly and clearly she looked at me and said – “When a child is injured like this, the whole world should see.”

– EMERGENCY’s Surgical Hospital, Erbil. March 2017

OTHER STORIES