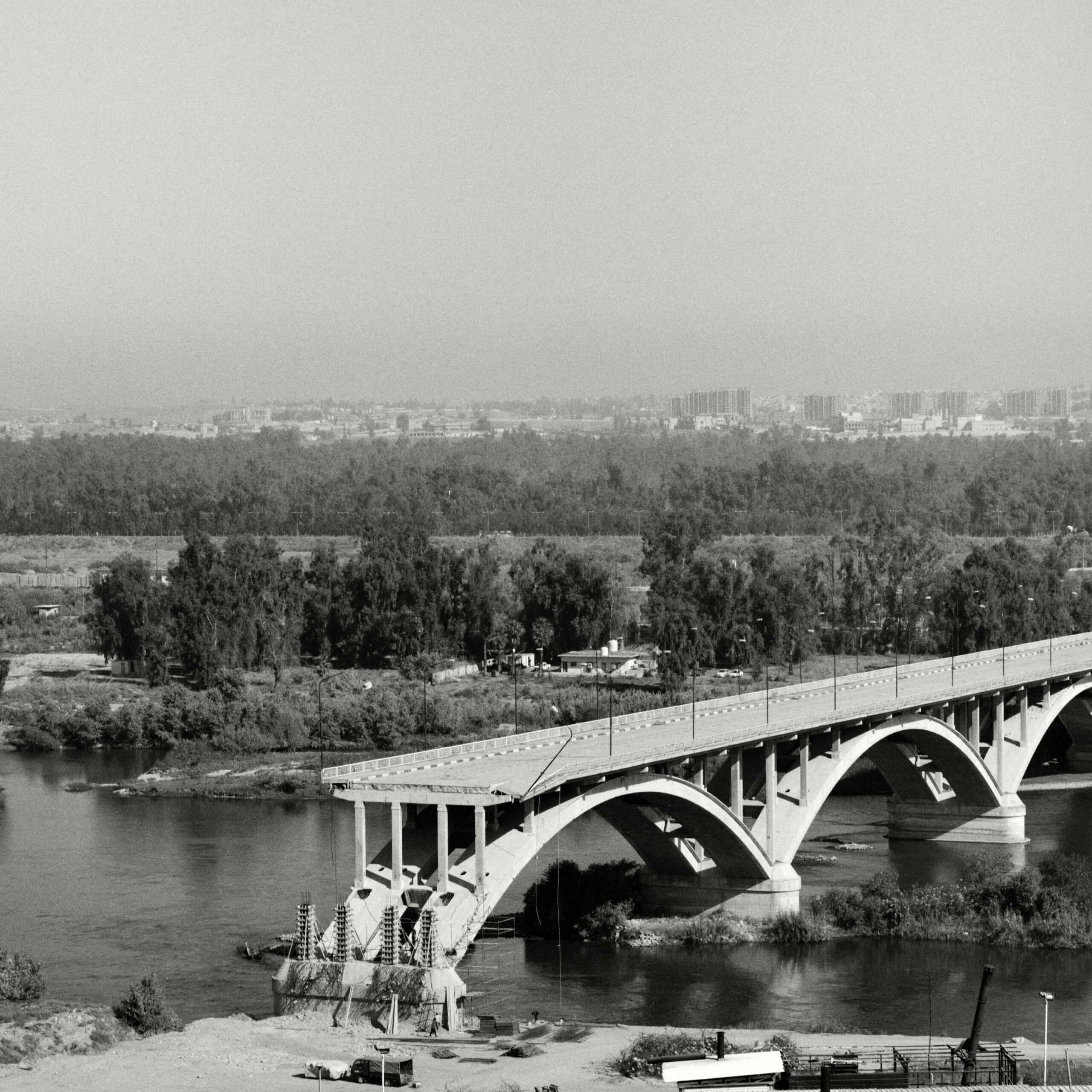

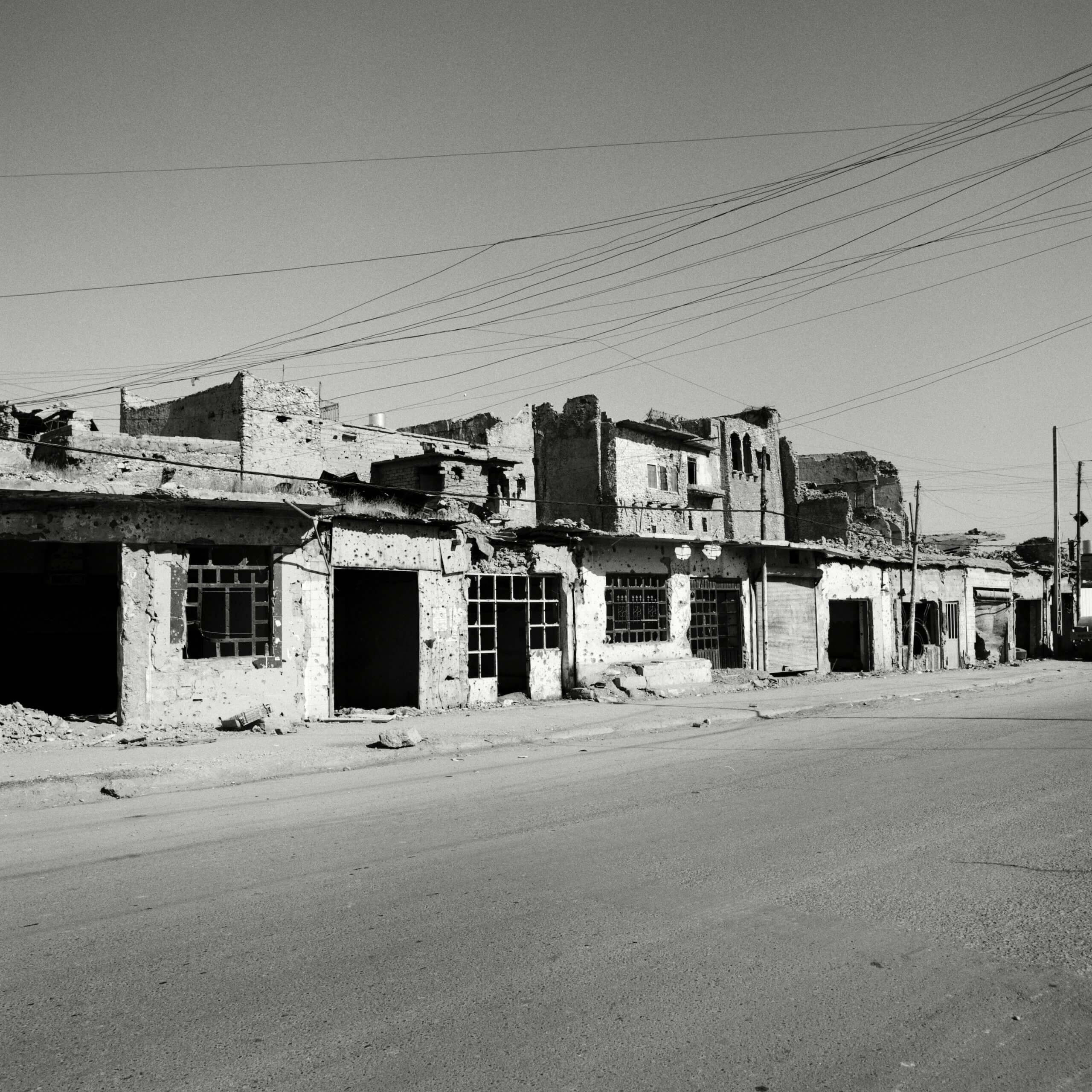

Mosul – A City of Ghosts

Mosul, Iraq

September 2019

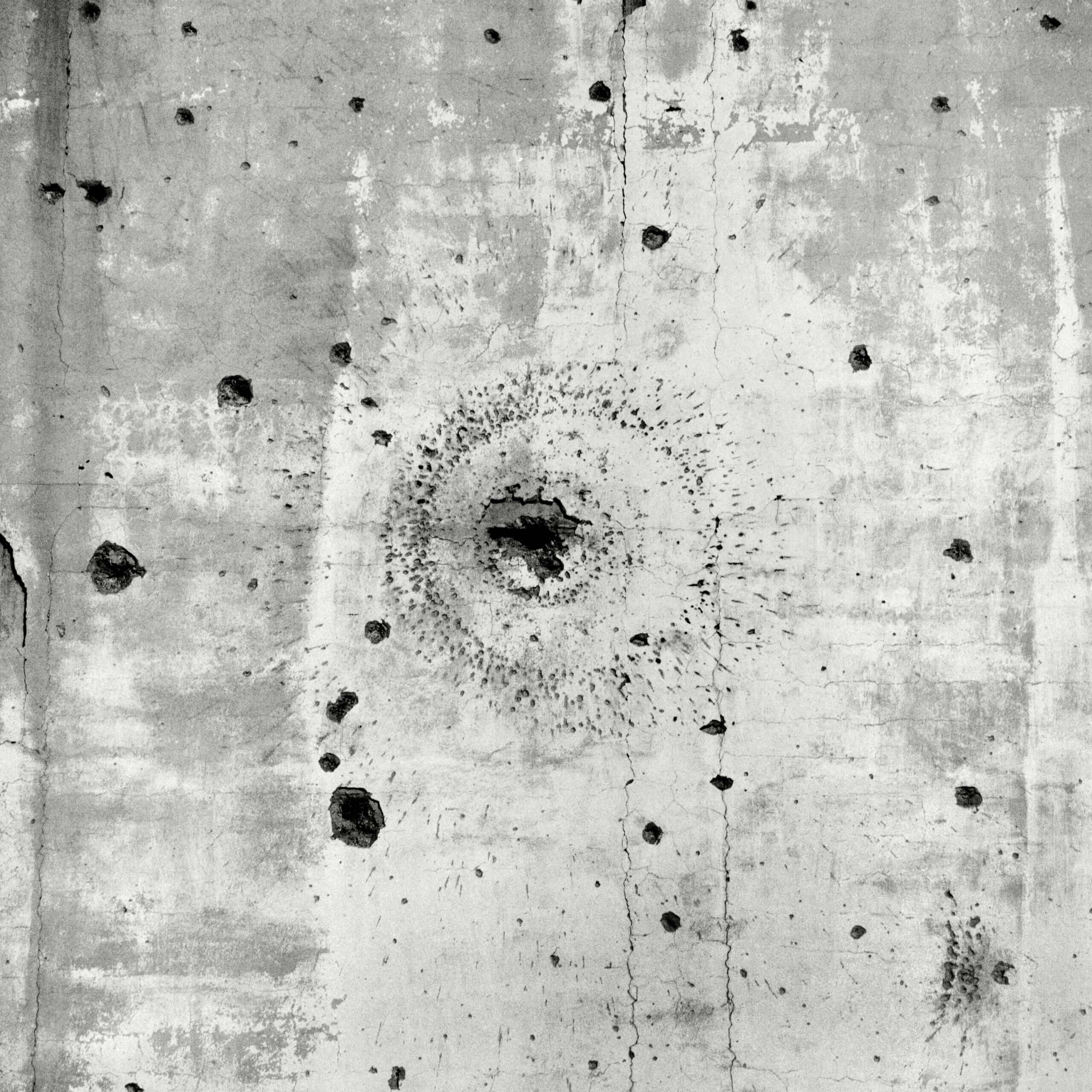

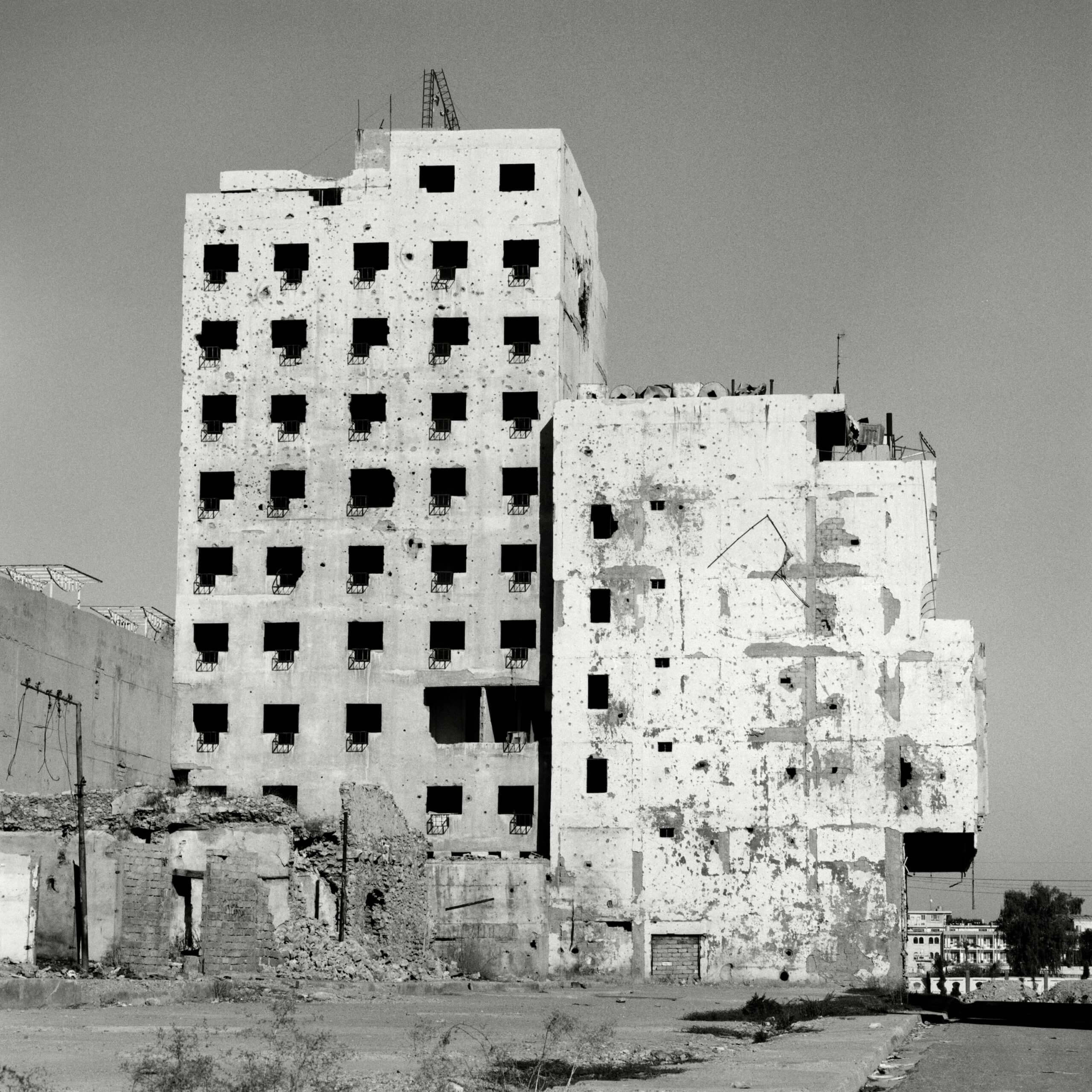

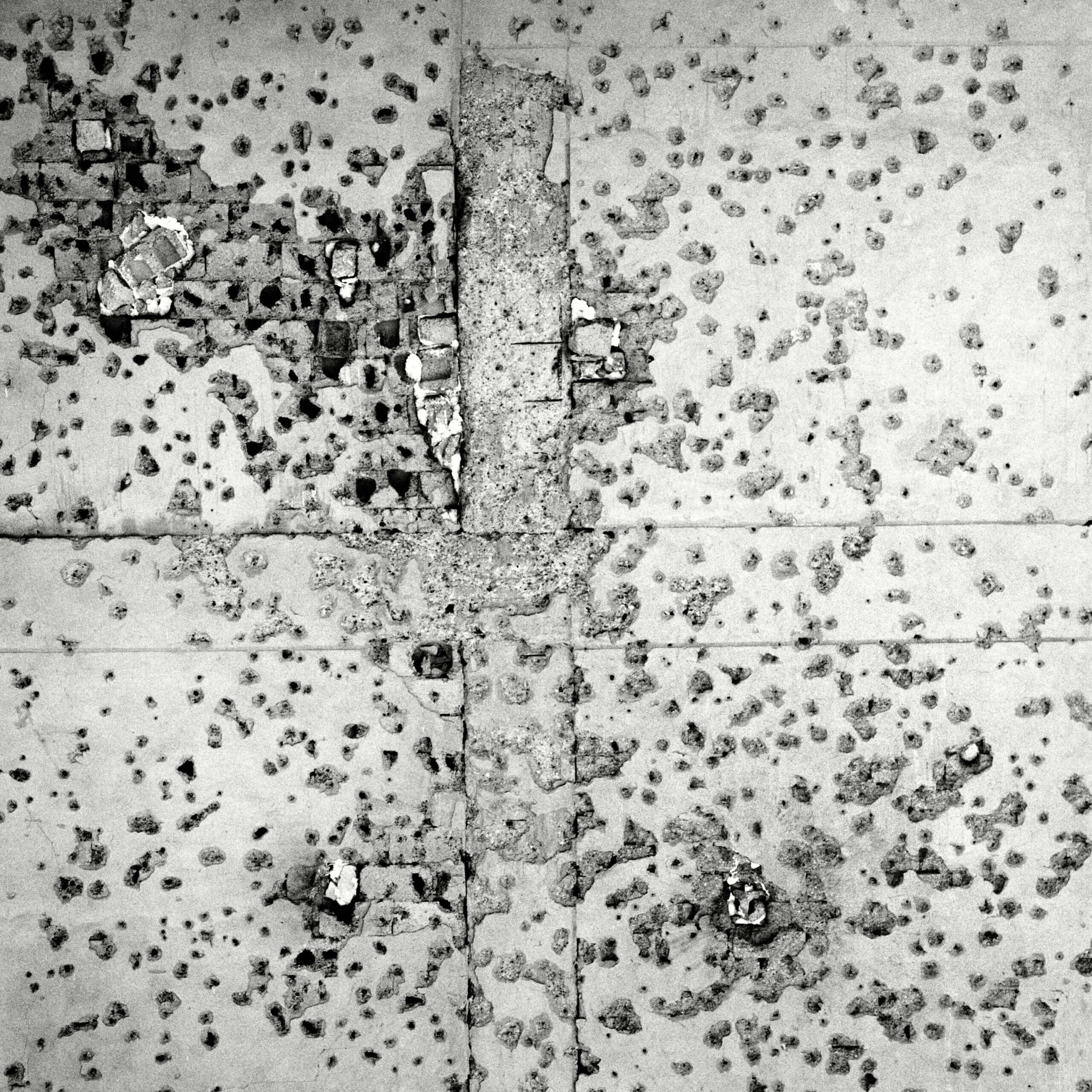

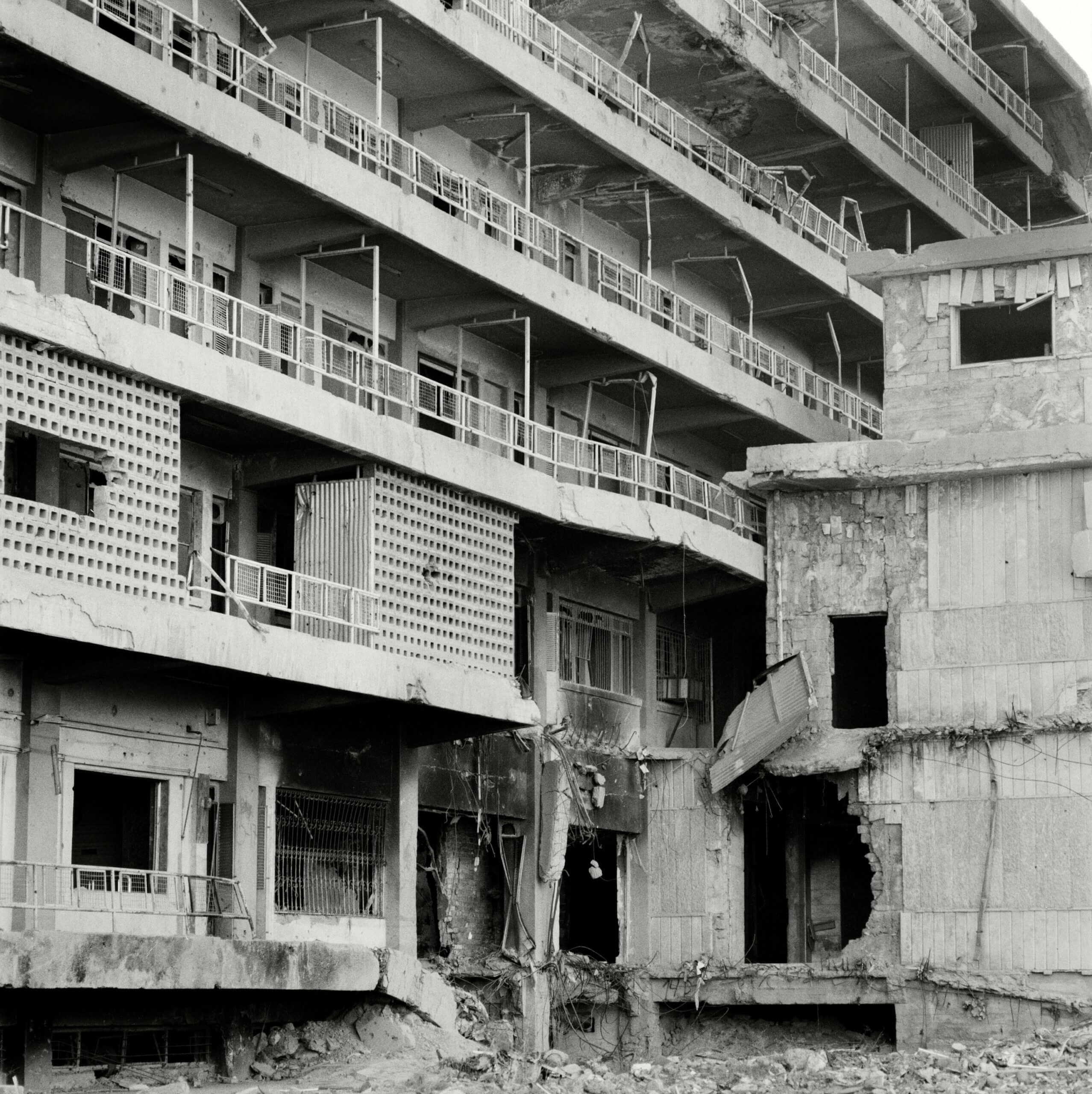

Trümmerfotografie: Mosul 2019

On 14th February 1945, as Kurt Vonnegut emerged from a meat locker beneath a slaughterhouse in Dresden, he was met with the scene of a moonscape of a burnt city. As he would later describe it in his novel, ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’, Dresden had been returned to a mineral state, a triumph of entropy:

‘because there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre. Everybody is supposed to be dead, to never say anything or want anything ever again. Everything is supposed to be very quiet after a massacre, and it always is, except for the birds.’

Vonnegut was witness to one of history’s most prolonged and destructive bombing campaigns: the Allied air war against Nazi Germany. For five years during the Second World War, the Allied air forces launched a sustained assault against Germany’s cities. Peaking in the war’s final three months, civilian populations were targeted by the weapons of mass destruction of that era. The campaign was to result in an estimated 600,000 casualties, and cities such as Dresden, Cologne, Hamburg and Berlin left as unrecognisable ruins.

“The aim of the Combined Bomber Offensive…should be unambiguously stated [as] the destruction of German cities, the killing of German workers, and the disruption of civilized life throughout Germany…. the destruction of houses, public utilities, transport and lives, the creation of a refugee problem on an unprecedented scale, and the breakdown of morale both at home and at the battle fronts by fear of extended and intensified bombing, are accepted and intended aims of our bombing policy. They are not by-products of attempts to hit factories”

– Arthur Harris, the head of RAF Bomber Command

At the end of World War II unprecedented destruction of Germany’s cities was widely documented by both German and other European and US photographers, including Hermann Clausen, August Sander, Herbert List, Richard Peter, Henry Ries, Edmund Kesting, Kurt Schaarschuch, Walter Hege, Robert Capa, Margaret Bourke-White, Werner Bischof, David ‘Chim’ Seymour, Lee Miller and Ernst Hass.

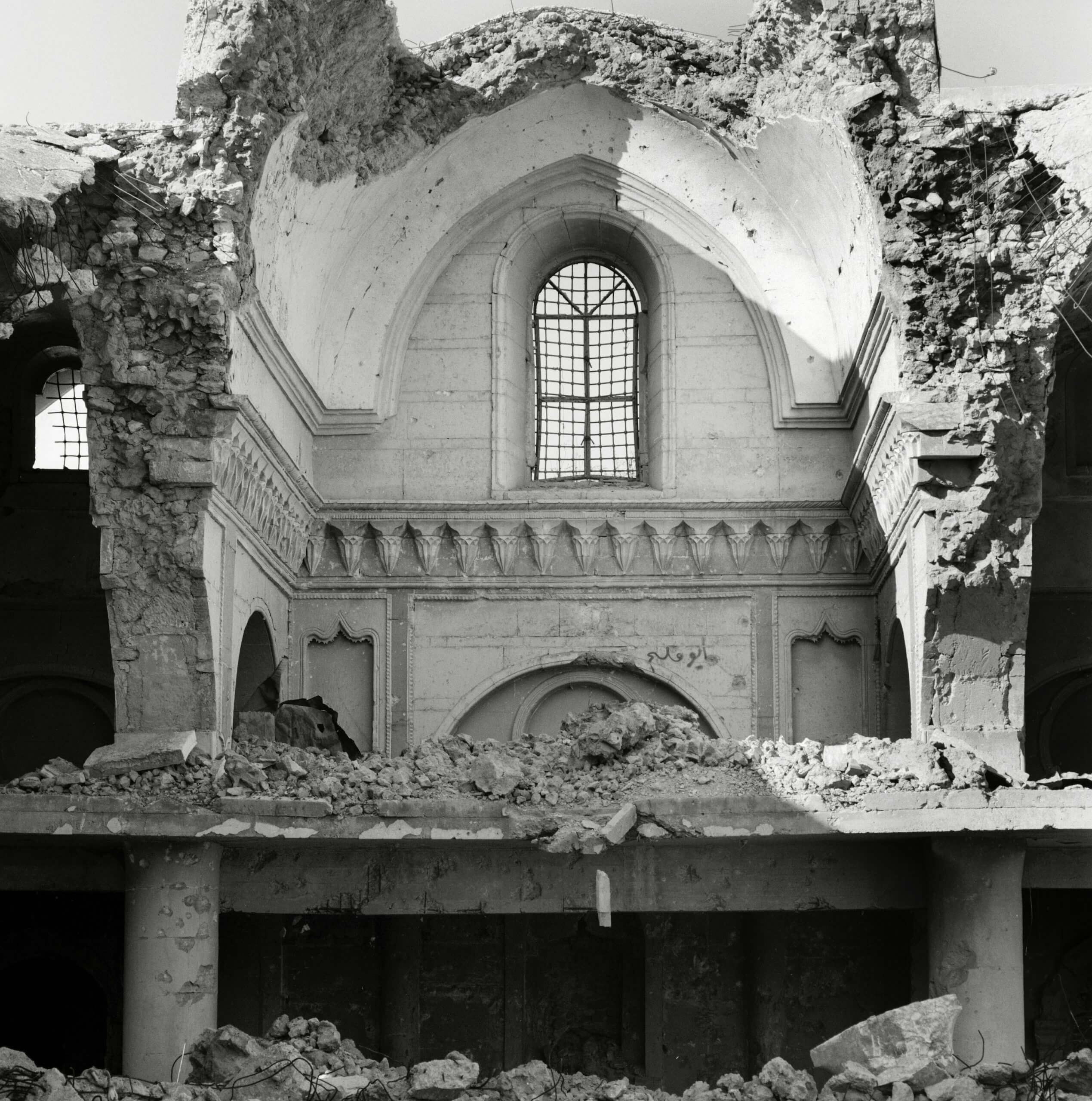

This documentation of the destruction of German cities in the immediate post-war years by these, and many other, photographers became known as Trümmerfotografie, quite literally ‘rubble’ or ‘wreckage photography’. The camera is the accuser through its framing and documentation. The images serving as witnesses long after the city is rebuilt.

‘Forming a subset of disaster photography, rubble photography (Trümmerfotografie) is a genre commonly composed of images depicting bombed and burned-out cities like Dresden and Cologne. It is cited when theorizing the contribution of such images to the politics of collective memory connected to Germany’s reconstruction and eventual reunification after the Second World War.’

– W. Taylor

In the years following the fall of Nazism, this ‘rubble photography’ allowed post-war Germans to begin to process their experiences of the war, death, ruination and defeat. These photo narratives spoke clearly of the traumatic experience shared by all Germans, an experience that many were unable to articulate through words. This was the apocalypse of a nation marked in stone.

Conversely, the response to this form of photography outside of Germany was to communicate the total destruction of a nation seen as the aggressor and cause of so much suffering, but in a way that represented the country as made of stone and not people. This imagery portrayed the destruction of Nazi Germany in a way that avoided Allied guilt about the suffering of its people.

‘I would suggest that this gesture is ultimately symptomatic of the role photography played in the western sectors as early as 1945. As a medium closely associated with legible mimesis, it could scarcely overlook the country’s most striking and unavoidable reality. Yet even as it succumbed to this realist inevitability, it declined to participate in constructing a pictorial grammar that might articulate or in some way signal the traumatic events which produced these piles of ruins in the first place. Instead, western Trümmerfotografie borrowed from traditional photographic approaches and transhistorical metaphors to give these visions smooth form and meaning, thereby suppressing their capacity to excite memory. This genre of photography essentially taught viewers how to see religion, art, and hope in vast material signs of an otherwise disorienting catastrophe. What one finds here, in other words, is the universalization of a historically specific case of destruction and suffering.’

– Andrés Mario Zervigón

In October 2016 Iraqi and Kurdish forces, supported by US-led coalition airpower, had massed on the outskirts of Mosul in preparation for an offensive to retake the city. Since June 2014 the city, Iraqi’s second biggest, had been under the violent rule of ISIS.

What followed was nine months of brutal fighting, according Lt. Gen. Stephen Townsend, the top coalition commander, it was the ‘deadliest urban combat since World War II’. The US-led coalition, which included a dozen partner countries, carried out more than 1,250 strikes in the city, hitting thousands of targets with over 29,000 munitions, according to official figures.

In parallel with Arthur Harris’ objectives which seemed to disregard civilian life, the then US Secretary of Defence James Mattis described policy during the fight for Mosul as having ‘shifted from attrition tactics, where we shove them from one position to another in Iraq and Syria, to annihilation tactics where we surround them… …civilian casualties are a fact of life in this sort of situation.’

To this day nobody knows how many were killed in the fighting but thousands, tens of thousands, died. What is clear, when you speak to anybody who was in the city during the fighting, is that no family was untouched. As a resident said to me, “there are over a million people living in Mosul, which means there are a million stories of loss. Nobody was spared.”

Documenting the civilian casualties from Mosul in early 2017, at a hospital run by the Italian charity EMERGENCY, had left a deep scar on my consciousness. In the months after the fighting ended, it was important for me to revisit the city to document the aftermath of the fighting. In February 2018, I wrote the following on my return as I drove through Mosul, nearly a year after the fighting had ended:

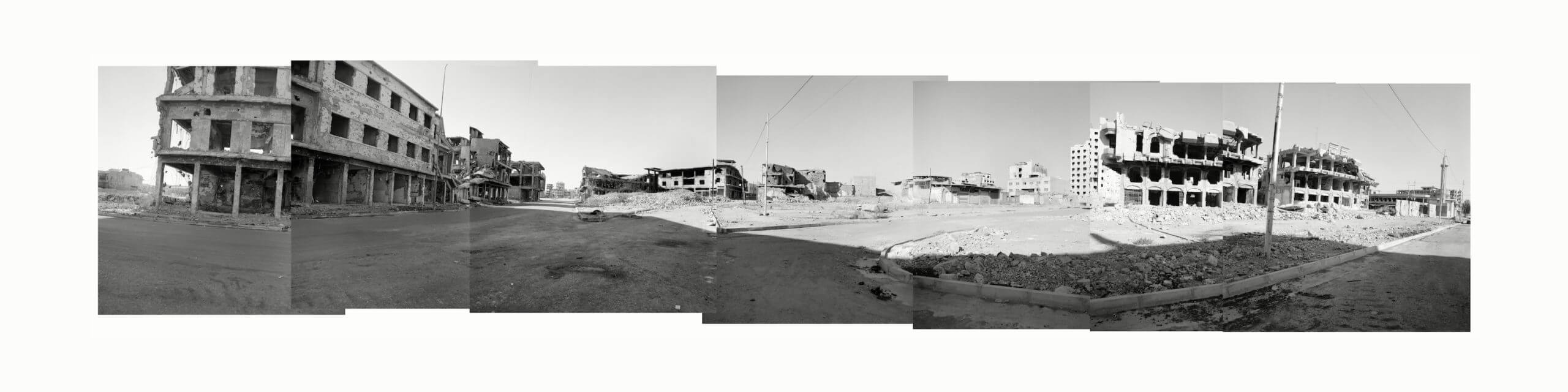

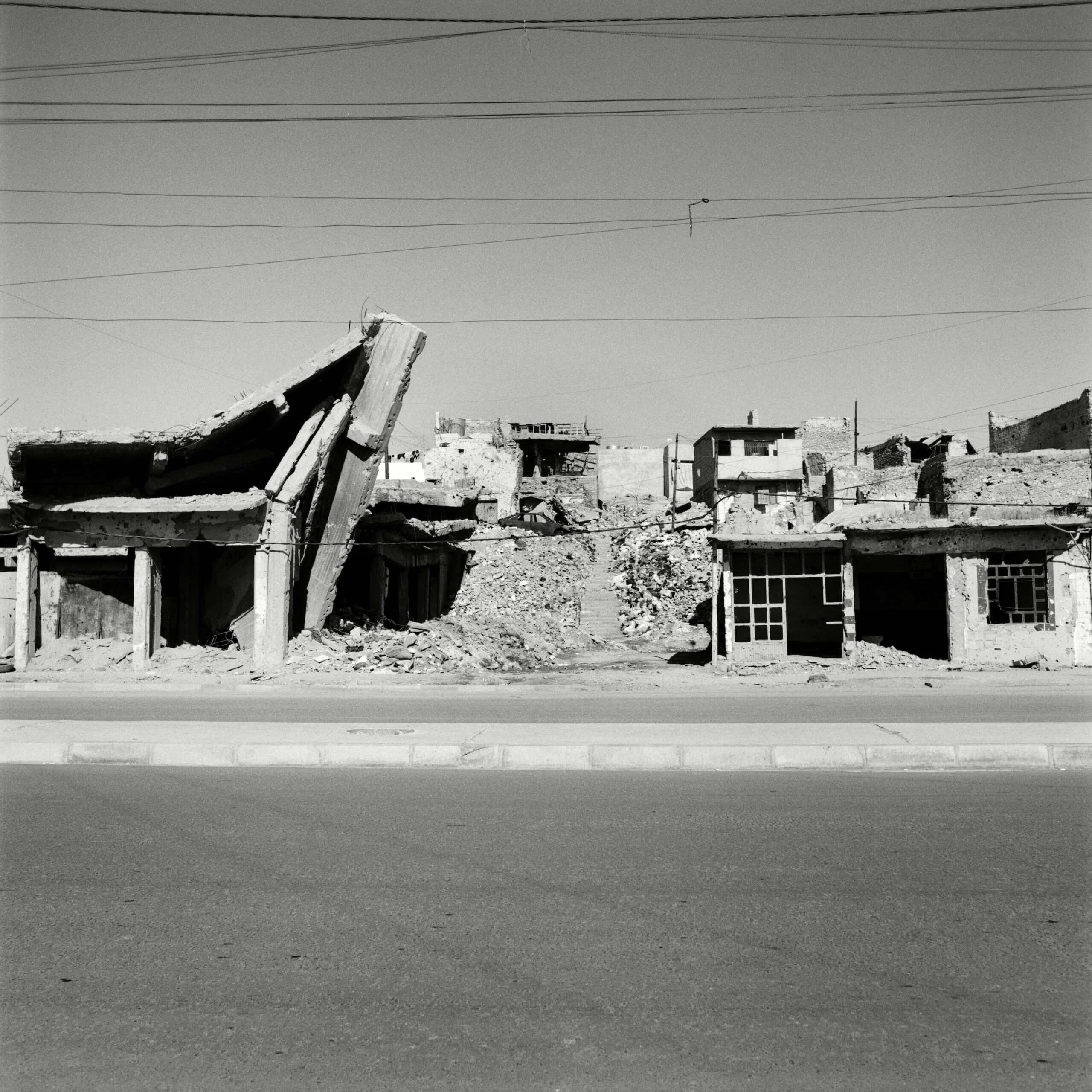

‘As a young student I remember seeing photos and film footage of the stark ruins of Stalingrad and Berlin, both destroyed during World War II. They seemed like monoliths to a past time, of total war. I never imagined this would be something I’d see in my lifetime, to be documenting the same scenes seventy years later. After all this is the era of smart bombs and precision strikes. But, as we drive through Mosul, I look from the car window dumbfounded by the scale of destruction. Air strikes, roadside bombs, mines, IED’s, tactical demolitions, rockets, tank shells, mortars, machine gun fire. Every munition known to man has been thrown at this city with the precision of a bulldozer. We drive for miles through street after street of destroyed building. After over a decade of reporting on conflicts, I have never seen anything on this scale.’

It was after this visit that people noted of some of my images that they could have been taken at the end of World War |I. It was from there that the series ‘Mosul; Trümmerfotografie’ was born. Seeing these parallels between the photographic work made in post-war Germany and what I had seen, I wanted to return to carry out a more formal documentation of Mosul’s destruction.

As it’s important for me that people and politicians make the connection between recent European history and current events in The Middle East, I felt the visual narrative of Trümmerfotografie would be the most powerful and direct way of connecting these events. As the Allies used total warfare to rid Europe of Nazism, so the coalition forces have used similar policies to rid Syria and Iraq of ISIS. Whether their rationales are justified or not, in both cases it is the civilians who have paid the price, while their cities and cultural histories lie in ruins.

In November 2019 I returned to document Mosul’s ruins to create this series. In much of the city the destruction is near total. The United Nations calculates that 80 percent of the Old City of Mosul has been demolished with 8,000 homes damaged or destroyed. The fighting has left eight million tonnes of debris behind. On my return, with the editing complete, in putting the images created on that visit alongside those made seventy-five years before, I see no difference. Nothing has changed, no lessons learned. Rubble next to rubble: silent witnesses to man’s folly, monolithic testimonies to war’s increasingly destructive powers and terrible human cost.

‘The bombing itself grows vague and dreamlike. The little pictures remain as sharp as they were when they were new.’

– John Steinbeck

OTHER STORIES