Return to the place of ghosts

London

May 2020

After stepping on an IED while documenting war in Afghanistan, award-winning photographer GILES DULEY spent 46 days in intensive care, much of it on a ventilator. For all the severity of his injuries, the most traumatic memories from his year in recovery came from that time. As Covid-19 put medics and support staff around the world under the very worst challenges and many thousands of patients through the same trauma, Duley returned to the wards that brought his life back from the edge to document a different frontline and a ‘war’ where humanity survives.

Throughout May 2020 I was asked to document the response to Covid-19 by Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust in three London hospitals: Charing Cross, St Mary’s and Hammersmith. From A&E to the laboratories, admin staff to ICU nurses, the first ward to be switched to a Covid-19 cohort to heart surgery, I saw the complex, multidisciplinary response to this crisis by the NHS.

With 13,000 staff employed by the trust, its switch to dealing with Covid-19 patients from early March was a huge undertaking. By mid-May it had cared for more than 1,300 patients, with 500 of those needing to be ventilated in intensive care units (ICU). And in those first two months, 400 had died from the coronavirus in the three hospitals.

After hearing stories of healthcare services being overwhelmed in cities around the world, what first struck me was the professionalism and calmness and, most importantly, the sense of a team working in unison, a team where every player is crucial. During the crisis many had volunteered to step into roles they were unused to: surgeons acting as support staff in ICU, junior doctors feeding patients and providing palliative care. Egos were set aside, with every member of staff offering to do whatever was needed.

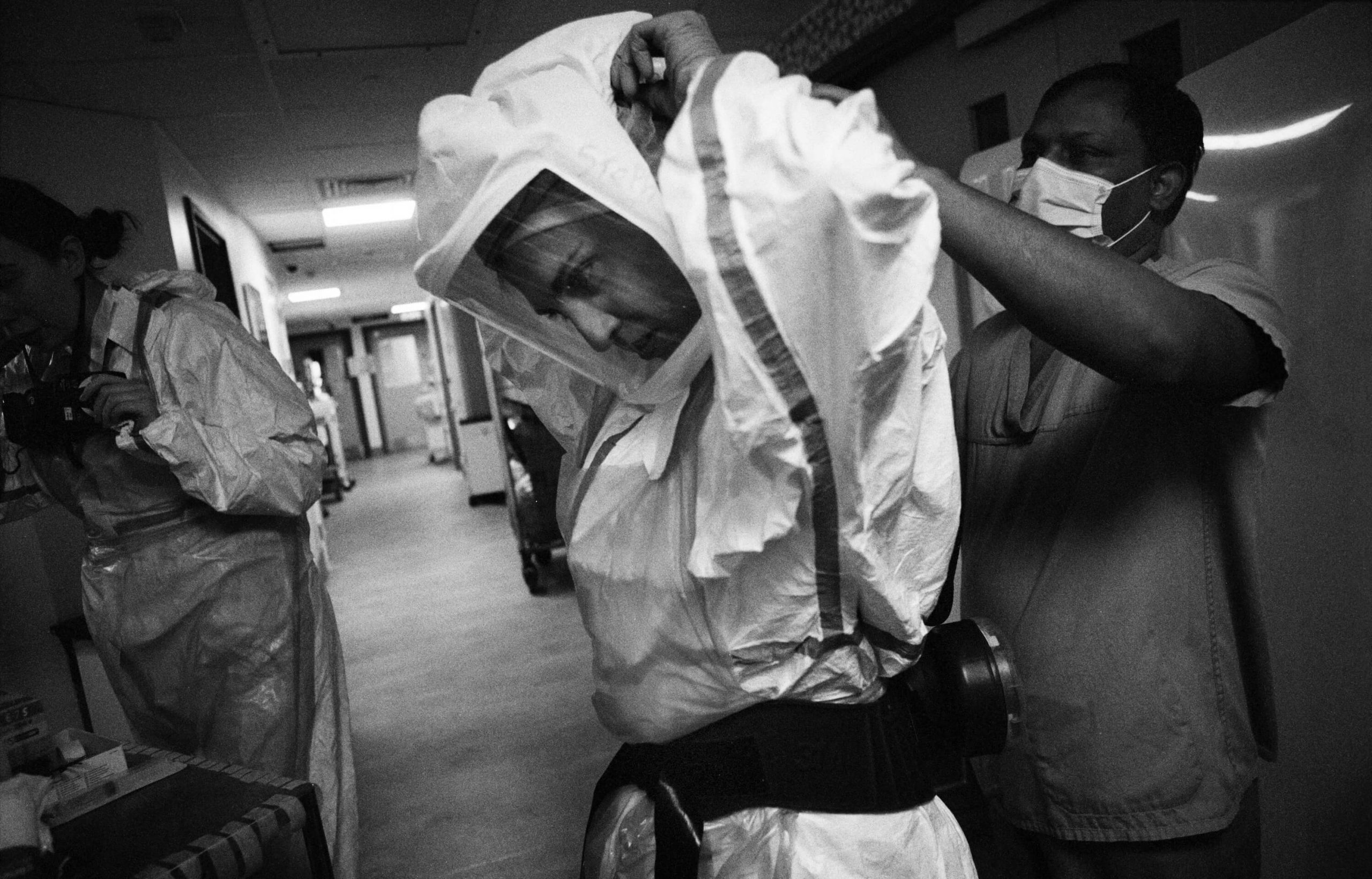

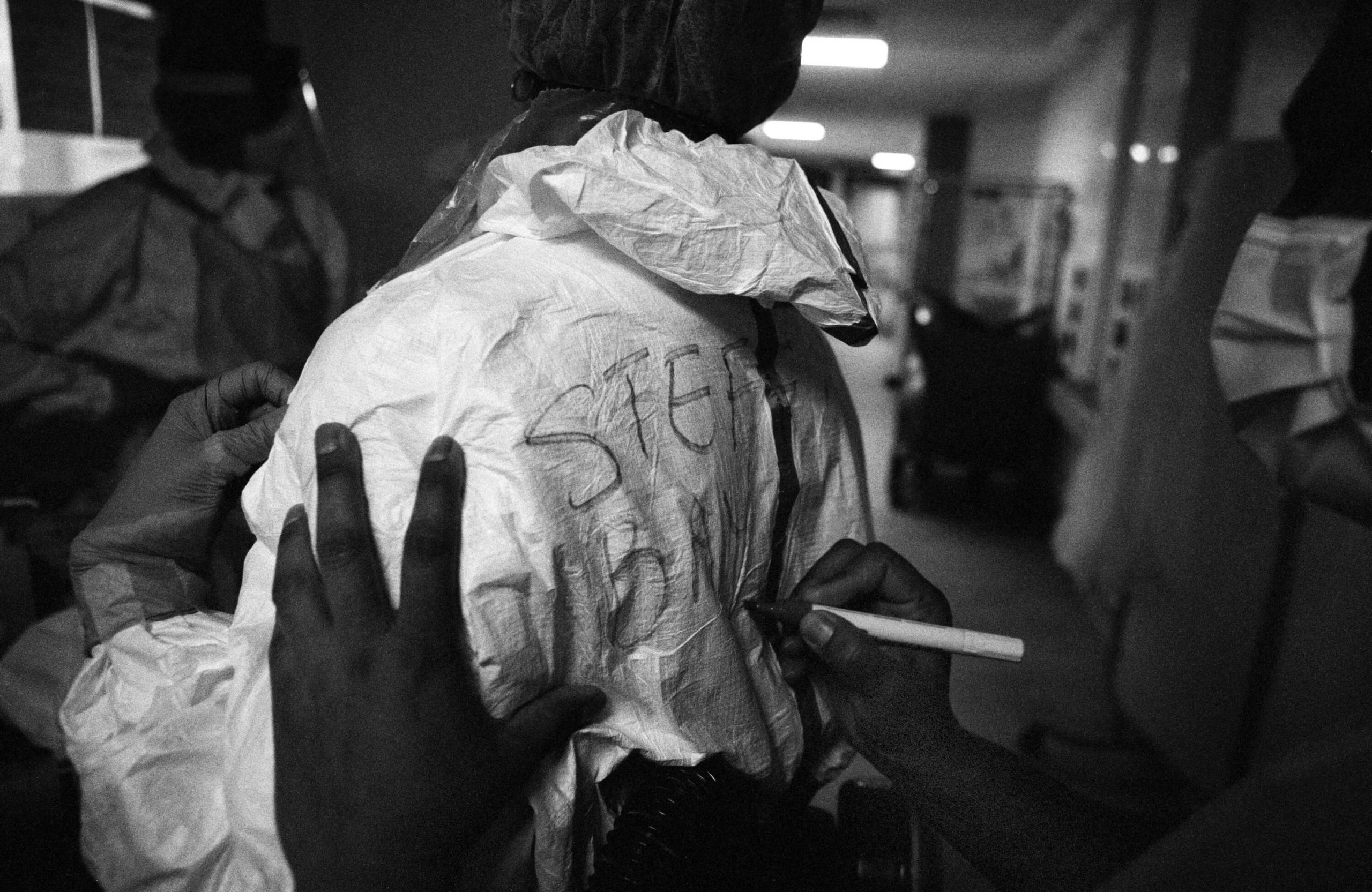

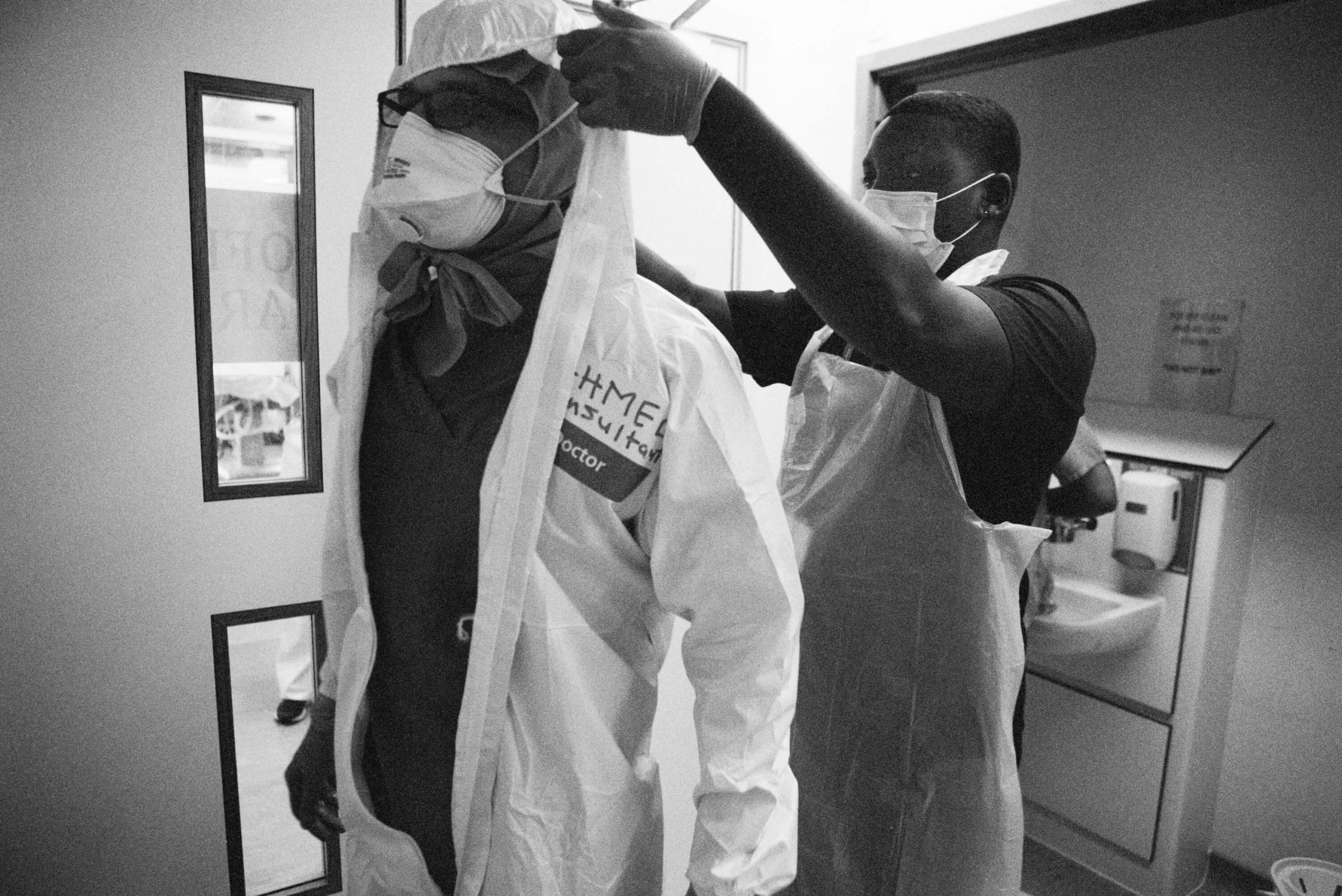

Behind the masks Stefania Nodari, an ICU nurse, dons PPE ahead of a shift at St Mary’s paediatric ICU (PICU); (below) a colleague writes Nodari’s name on her back. In full PPE its virtually impossible to recognise colleagues and, for patients, being unable to see carers’ faces is one of the most disturbing realities, 8 May

It’s something everybody within the NHS is proud of and a story they wanted told. After one meeting a nurse pulled me aside and said, “Please make sure you document the work of the cleaners. They’ve been amazing.” This after a junior doctor asked me to make sure I focus on the nurses. Everybody is full of praise for their colleagues. Again and again I was told, “I only got through this because of the support of my team.”

This project had particular meaning to me. Following an accident in 2011 – I stepped on an IED while in Afghanistan working as a photographer – I spent a year in hospital, much of that time in wards of these hospitals. Some of the staff I was working with were responsible for saving my life. Indeed, it was they who asked me to come and document the hospitals during this unprecedented time. It was the 46 days I spent in an intensive care unit, much of that time on a ventilator, that left the most traumatic memories and returning was not an easy decision. The nightmares from that time have never left me.

On 7 May I joined the team during their night shift in the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) at St Mary’s Hospital. As Covid-19 spread and beds were in short supply, the ward had switched to an adult ICU. To enter an intensive care unit at night is to enter a place of ghosts. It is a place between life and death, where patients’ lives are maintained by machines and drugs that take over many of the body’s functions. The doctors and nurses, like modern-day alchemists, control the ventilators, drips, PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter) lines, feeding tubes, medications and monitors that sustain life. It’s a process that doesn’t stop: even throughout the night, a patient’s bloods and vital signs are recorded and analysed and adjustments are made. There is a constant whir of servos, bleeps and alarms; lights flash and monitors record the slightest change in vital signs.

This work was hard enough before Covid-19, but PPE adds a physical element to the task. Scrubs, gloves, apron and disposable apron, shoe covers, mask, visor, second gloves and then tape must all be donned before entering the unit. It’s unbearably hot and hard to breathe through the mask; even the simplest of tasks is exhausting. The staff are pushed to the limits of endurance while having to stay alert, as a moment of distraction could prove critical to a patient’s survival. As the PPE takes so long to remove, it’s impossible to stop for a sip of water or to take a toilet break. The teams worked 12-hour shifts, often with only one break.

A Covid-19 intensive care unit is brutal: the stark environment, the physical strains, the knowledge that some patients won’t survive. Yet despite all this, what I found in these units is the greatest of humanity. The staff went about their work with professionalism and focus. They are the strongest of teams, all supporting each other and, most movingly, they treat their patients with such compassion and dignity.

As the doctors did their rounds, even though most patients are in induced comas and those conscious are barely responsive, they took their time and talked to their patients, held their hands, comforted and encouraged. The nurses, despite being under so much pressure, did the same, always explaining what they were doing, looking into the eyes of their patients as they injected drugs through the PICC lines or took more bloods.

One patient had been taken off the ventilator and was slowly waking from his induced coma. Confused and disorientated by the drugs still in his body and unable to speak because of a tracheostomy, he tapped on his phone. No personal items are allowed in ICU – the staff must leave their mobiles and even ID cards outside – but the one exception is each patient has their phone with them.

Left: Even when patients are comatose, staff speak to them and hold their hands. The psychological impact of a stay in ICU can be long-lasting and human contact is vital to recovery, St Mary’s PICU, 8 May

Right: Dr Qureshi clasps hands with a ventilated patient, St Mary’s ICU, 8 May

As no family members are allowed to visit, this is their only connection to the outside world and their loved ones. He tapped the phone again and Nicola Reid, a senior sister on the ward, picked it up. “You want to speak with your family?” Reid asked. The patient’s eyes widened, pleading silently. Sister Reid tried to unlock his phone but was unable. The patient was still too weak to do it himself, so the nurse placed it back down beside him and squeezed his hand. “We’ll figure it out. I promise. Till then I’m here.”

“This pandemic felt like a huge wave that was going across the world and it was going to hit us like a tsunami. I think that time waiting was the most terrifying thing for me,” explained Dr Sabeena Qureshi, a consultant paediatric anaesthetist at St Mary’s Hospital who had been accompanying me on my night on the PICU.

“In our network we were hearing of hospitals that were suddenly, overnight, overwhelmed by patients that were intubated and put on ventilators and we knew it was going to happen. We were ready, we were set up and then it didn’t hit for about a week and we thought, ‘Maybe it’s not going to happen.’ But that was the calm before the storm – the tide going out before the tsunami hit. And then it hit.

“Although we had been told by our counterparts in other countries, ‘These patients are really sick,’ I don’t think we really understood. Then the first patients came and we knew. We knew as doctors and nurses that whatever we did, these patients were getting worse. We were overwhelmed by the number, how sick they were and that they all came in at the same time. We thought we were ready and then we realised we had no idea. I don’t think we realised quite how infectious the disease was and quite how devastating it was.

“It was amazing how the nurses coped, because they are the majority of the staff in ICU. It was a very coordinated effort. And although things were changing rapidly day by day, we were ready to adapt. In the morning our plan was maybe X-Y-Z; by the afternoon we’d be back to the start of the alphabet and off again, rewriting the book.”

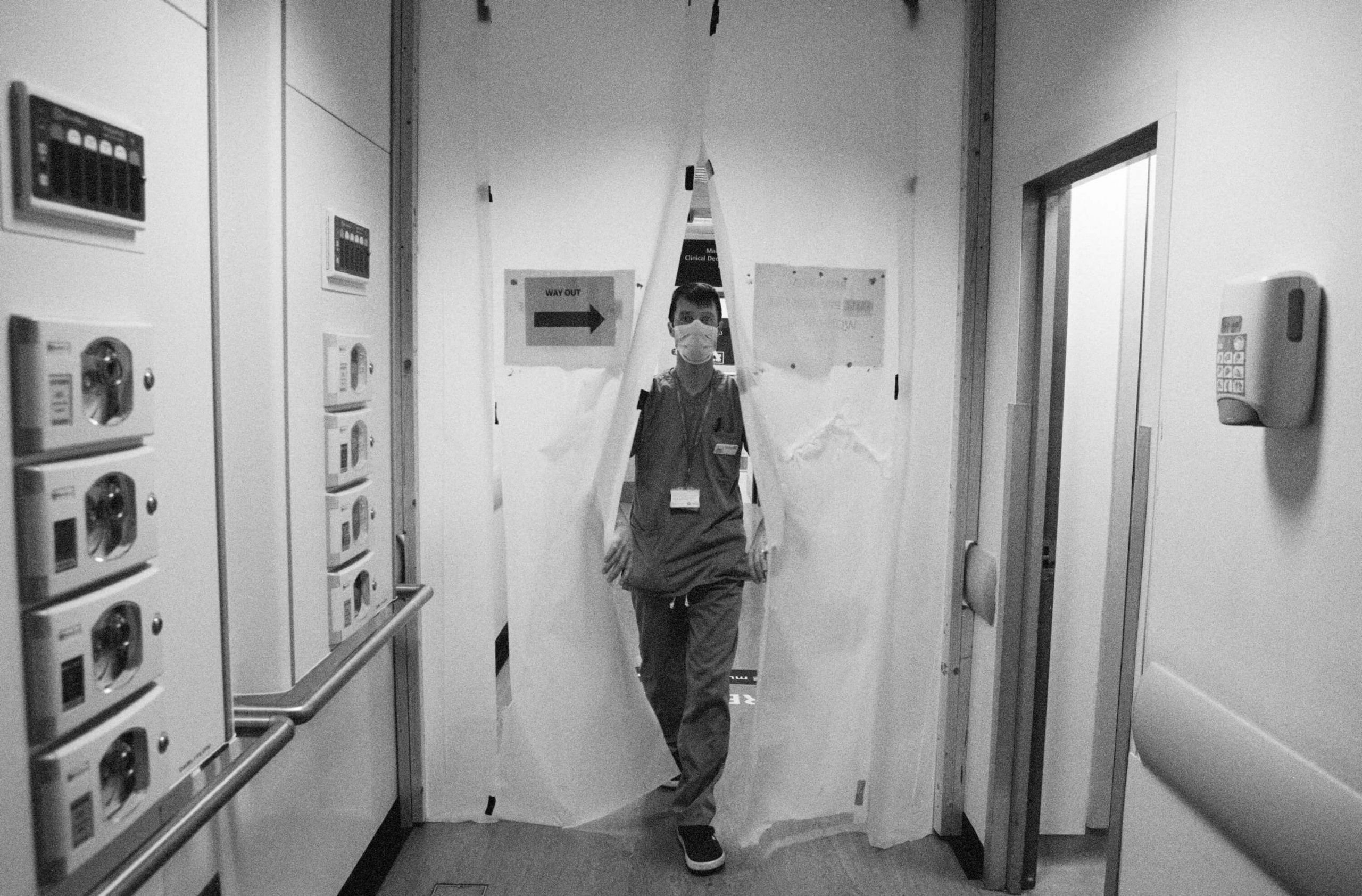

Left: Emergency technical assistant João Carlos Ruivo Alves steps into the ‘red zone’ (a designated ward for suspected Covid-19 patients) at Charing Cross A&E, 11 May 2020

This first wave did get close to overwhelming the NHS. This virus is complex, aggressive and still not fully understood. And the teams were dealing with the realisation that what started as a sprint was turning into a marathon. The analogy most used when describing it to me is the Aids epidemic: patients often present with confusing and unique symptoms.

In the worst cases it seems it’s the body’s “cytokine storm” response to the virus that proves fatal. The most serious cases are a puzzle that deeply challenges the clinical staff. I’ve documented frontline hospitals in warzones, Ebola outbreaks and worked with medical NGOs in other humanitarian crises and this virus is deeply worrying. This is not the flu. An uncontrolled second wave or a slight mutation of the virus could be catastrophic. As for the potential devastation it could cause in developing countries or packed refugee camps, it’s unimaginable.

Left: Emergency technical assistant João Carlos Ruivo Alves takes blood in the ‘red zone’ of Charing Cross A&E, 11 May

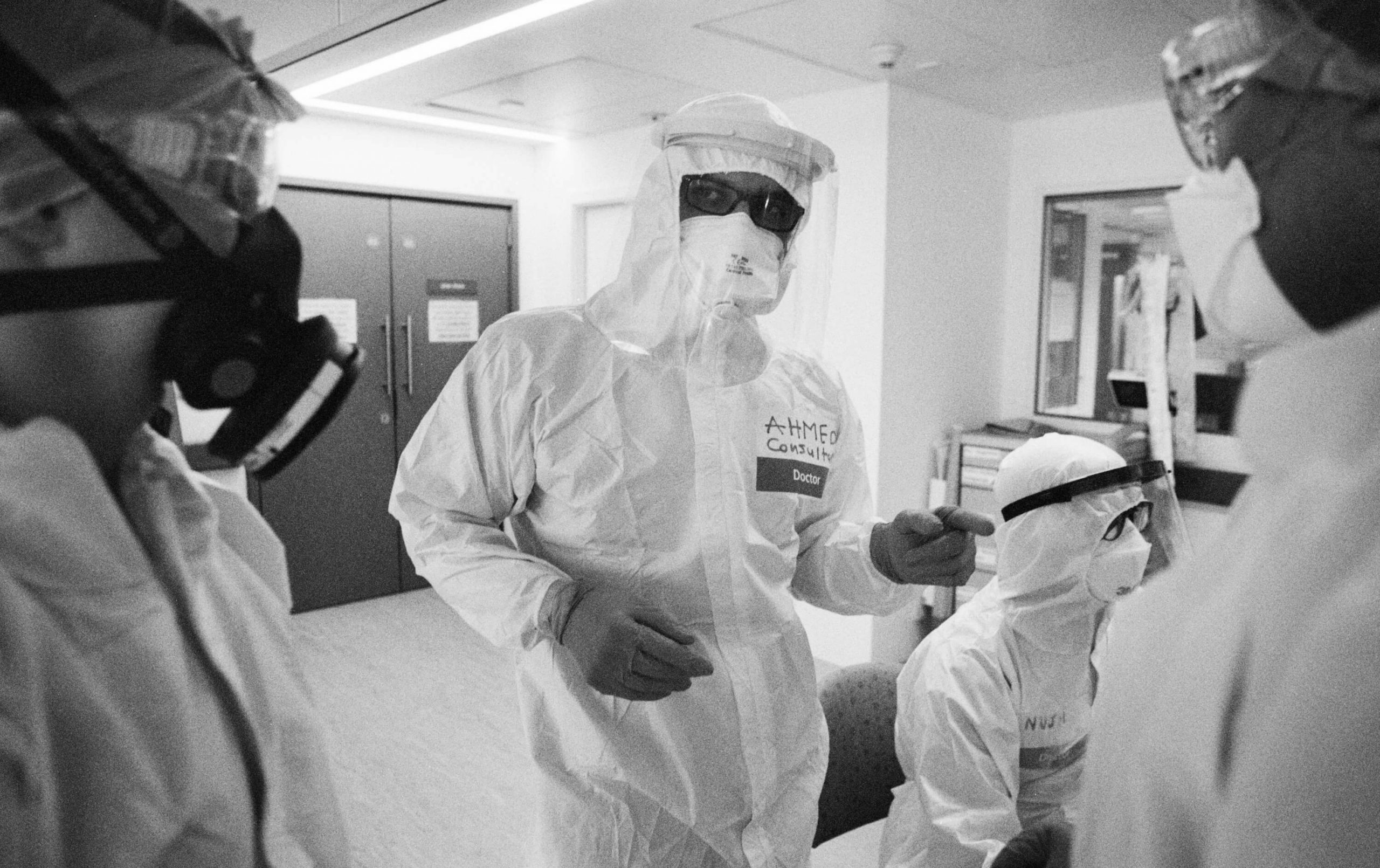

At the end of May, as my project drew to a close, I joined Dr Ahmed El Haddad, an intensive care consultant at St Mary’s, as he did his ward rounds. One of the patients needed the filter in his ventilator changing. These filters are in the tube between the machine and the patient and in a few days they can age and need replacing. In normal times it’s a complicated procedure, but with Covid-19 it’s potentially deadly as the compressed air is released. So the ventilator is stopped, the tubes are clamped at either end and removed and a new circuit is fitted. It’s a complicated procedure that has to be done in seconds.

As the team of three began the procedure, the patient’s vital signs started to crash. As Dr El Haddad explained afterwards, the Covid-19 patients are so fragile that even a routine task such as this can make them unwell in the time it takes to change the filter. The team worked with the precision and speed of a Grand Prix pit crew, but were visibly concerned when the vitals continued to weaken. As the ventilator was turned on, there was a moment when the team just watched the monitors in silence, then emitted audible relief as the oxygen levels, blood pressure and heart rate returned to safe levels.

As the team moved on to the next patient I stayed. Being on a ventilator means having a painful intubation down your throat, a tube down your nose to feed you, a bag to collect your diarrhoea, days or weeks under anaesthesia while painkillers and sedatives are injected. It’s a traumatic experience that can leave longlasting medical complications and psychological trauma. Watching them change the filter really hit me: I felt a sense of panic inside my PPE. It was hard returning to conflict zones after my accident, but I had a far greater fear returning to an ICU and now that unease was flooding back.

Nine years ago, when I was on a ventilator, something had gone wrong during this same procedure. As they tried to connect the new tube a fixing had jammed and what would normally take seconds had taken minutes – minutes during which my brain had been starved of oxygen. That evening the doctors had spoken to my family. With my body already coping with multiple organ failure and this latest incident potentially leaving me with brain damage, they were asked to consider if they wanted my life support to continue. My brother simply answered, “While he’s still fighting, we will keep fighting for him.”

Now, as we continued to do the rounds of the ward, I lingered for a moment as the doctors moved on from each bed with its comatose, ventilated patient and in my mind I found myself muttering, “Keep fucking fighting.” It was a ridiculous response to such a desperate situation, but being there was a stark reminder of the fragility of life, of how close I was to losing mine, of the heartbreaks and loss being felt across the country.

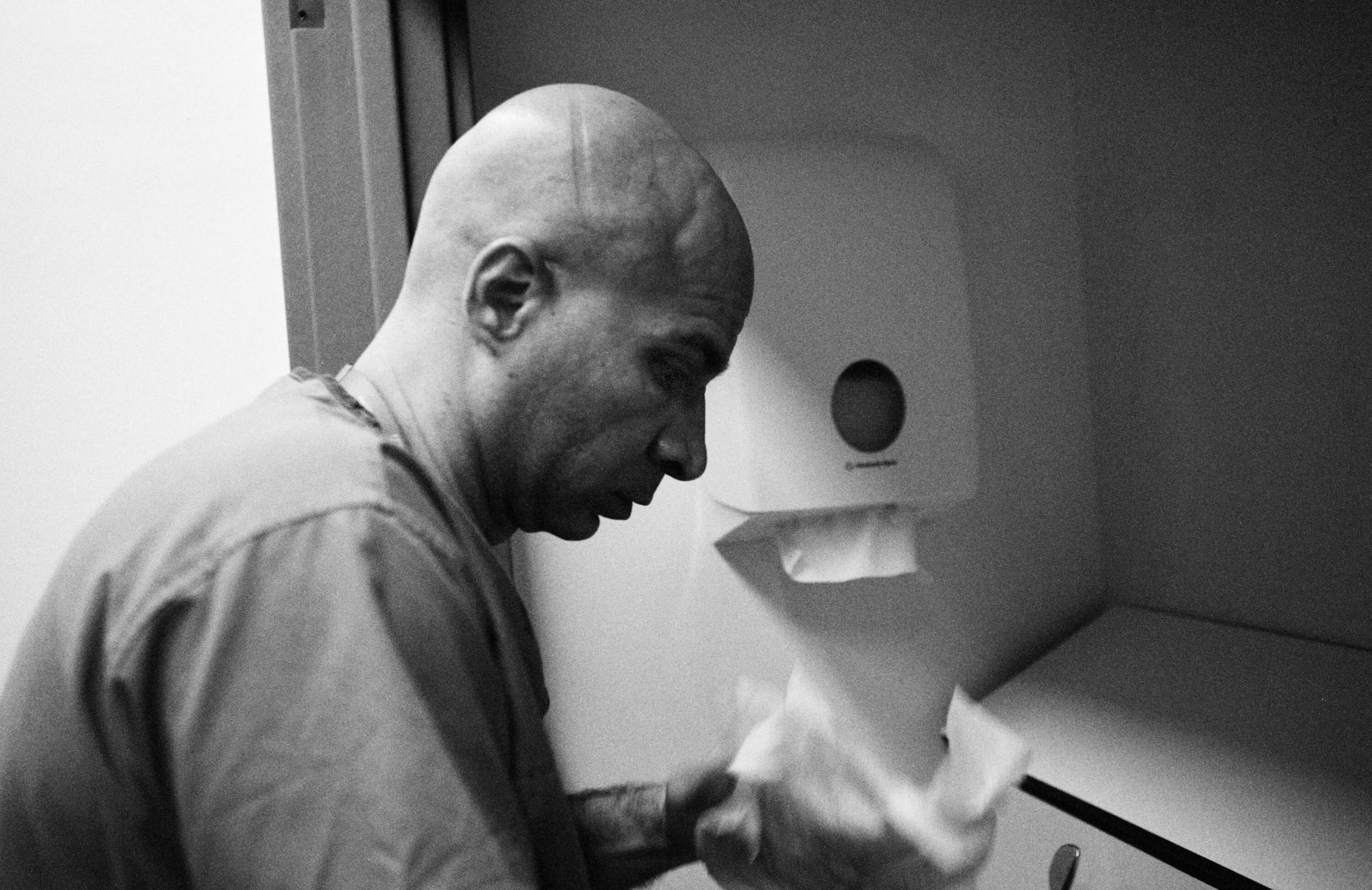

Simple tasks take on new complexity once suited in PPE. From using the phone to measuring doses, the layers of protection dull dexterity, vision and hearing, St Mary’s ICU, 21 May

Cleaners, porters, nurses, doctors, admin teams, lab technicians: all the staff had been under huge physical and emotional stress these past months. Many had been unable to live at home and had not seen their families for weeks. “We’ve been distant from our families and our normal support mechanisms at a time when the normal challenges of working as a doctor have been amplified and confounded by all of the emotional fear and turbulence that we’re facing as individuals in a pandemic, not just as doctors,” explained Phoebe Verbeeten, a junior doctor at St Mary’s Hospital. “And I think it’s really important that I continue to identify the repercussions of that and address them. Because I don’t want to look back in a few years’ time and say, ‘I felt lots of things I coped with and, actually, what I should have done is looked at them and processed them appropriately.’”

Yet despite their monumental efforts and the pressure they were under, the majority of the staff I met working on these wards were uncomfortable with the word “hero”. It was, of course, used with best intentions, but they were worried there was a danger we forget that the staff are human. Many pointed out that they were working long, exhausting hours, often understaffed and not valued, long before Covid-19, and, that besides, this is their job. Others worried that when politicians call them heroes, they are suggesting the staff made the choice and expected the sacrifices caused by political mistakes.

Right: Jacinto Mendoza, a cleaner, with staff nurse Cora Cosmod, Charing Cross Hospital A&E, 11 May

The NHS is an incredible mix of nationalities, with staff from more than 200 countries. More than 14 per cent of the NHS workforce in England classify themselves as not being British and in London those numbers are higher; 16 per cent of staff from Imperial College Healthcare Trust are from the EU. In its diversity lies its strength. Yet despite the incredible dedication shown by the doctors, nurses and support staff from outside of the UK, their right to remain in the UK is not guaranteed.

Politicians and media constantly use the analogy of this being a war and the NHS staff being on the frontline. I have witnessed war and I can tell you that this is the opposite. War is devoid of humanity. It is inhumane and cold. What I saw in these hospitals is all that is good in humanity. The hospital staff, despite all their challenges and fears, went about their work with calmness, professionalism, compassion and dedication.

Right: ICU physiotherapist Genevieve Price (top) and registrar Osama Shahid and nurse Leanne Dolman (above) wash hands and remove PPE after shifts at St Mary’s. This is when the risk of cross-contamination is greatest so all must follow strict ‘doffing’ protocol, 21 May

It was the details of their work that impacted me the most. The intimacies of shaving and washing Covid-positive patients, sitting holding their hands as they die, buying iPads to connect isolated patients with family: these moments went beyond their work. While the last thing I’d ever want to do is contradict the staff I met, and I do agree that just doing your job does not make you a hero, the manner in which you do it can.

Make no mistake, many of the staff were terrified while working during the first days of the crisis; some cried when they heard their wards were being switched to “red zones” (designating them for suspected Covid patients). Yet despite this, they still treated the sick with dignity and compassion. As one nurse told me, despite the risks of working with Covid-positive patients, “I did the job exactly the way I always have. I will care for my patients the way I’ve always cared for them.” These staff are the best of us. I feel humbled to have witnessed their work.

As I left on my final day I asked Dr El Haddad if he thought there would be a second wave. “I’m an optimist, so I’m hoping that this wave has settled. But we are planning to deal with another similar, or even worse, wave. And I think that the whole country’s trying to prepare for that.

“It’s the biggest fear: how am I going to go through this again? Let’s just pray there is no second wave, but if there is, those feelings will surface again. Because you know what’s coming, you know what you have been through and I know I don’t want to go through this again.”

Being here was a stark reminder of the fragility of life

OTHER STORIES