Scars from a Forgotten War – the Legacy of Landmines in Angola

Luena, Angola

April 2018

Minga was excited by her new toy. She had been walking back to the cassava field with her grandmother under the heavy midday sun when she remembered she’d left her plate by the bridge where earlier they’d stopped for lunch. She turned and ran back, but the plate wasn’t where she left it. She stooped down and began looking amongst the reeds and wild flowers that grew by the bridge. That’s when she discovered the new toy.

At dawn, when they’d left the village, her grandmother had told her not to come. “You worked all day yesterday, and you must be tired”, she said, “rest today.” But Minga, despite being just six years old, was already a headstrong young girl, and she went with her grandmother anyway.

And now she was glad she had, because of her discovery. Minga had never owned a toy, in the village they made do with sticks, or a broken wheel, this though was something different. It was green, mental and shaped like a small tin, the kind of tin that may have been for sardines, Minga thought. She wanted to show her brothers and sisters, so she picked it up to take home. As she picked it up she noticed on one side there was a clump of dirt, so she tried to clean it off with a stick, but the mud was caked like concrete by the relentless sun. Looking around she saw a rock by the river and thought she could use that to know it off. Once, twice, then as she hit the metal tin against the stone for a third time, her toy exploded.

The explosion blinded Minga and her left arm was severed at the elbow. It was June 2009.

________________________________________________________

Think of a major war in the last fifty years, and it’s doubtful you’d think of Angola. Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria – Angola is in many ways the forgotten war. Yet it was one of the most violent and long lasting of the 20th century and by its end in 2002 an estimated 2 million people had died. Sparked by a fight for power between two independence movements following the end of Portuguese colonial control in 1975, the Angolan war, much like Vietnam, became a proxy fight in the far bigger global cold war. The two sides, the MLPA and UNITA, were supported by Cuban and South African troops respectfully; with funds and arms flooding into both sides from the USSR and the USA.

It was a particularly brutal war, with targeting of civilians, the use of child soldiers, and atrocities committed by both sides. Yet the world was happy to keep arming all factions of this oil and diamond rich country. As late as 1989 George H W Bush, had promised the rebel UNITA leader Savimbi – “all appropriate and effective assistance.”

In fact it was to be the death of Savimbi that was to effectively bring the war to an end. A near mythical figure, his charisma and power had been the core of UNITA. In 2002 he was injured in a fire-fight with Angolan government soldiers in Moxico province, and died soon afterwards. Just six weeks after his death, a ceasefire was signed.

But peace did not bring stability and improved living for all. Visit Angola province today and you find a still deeply divided society. Whilst oil and diamonds have brought wealth to some, in many parts of the country, people live in deep poverty.

Moxico is Angola’s largest province, situated in the far east of the country, on the borders of Zambia and DC Congo. It covers and area the size of Great Britain, yet has a population smaller than Nottingham. During the civil war it was often the centre of the guerrilla campaign, and as a result much of the infrastructure was destroyed. Only recently were new roads built and the major bridges replaced.

For people living in Moxico the civil war has cast a deep shadow, economically, and in the thousands of refugees and internally displaced people, who are still returning. But there is another deadly legacy that haunts Moxico 16 years after the war ended – landmines.

It is estimated that 500,000 to more than a million landmines were laid during the civil war, with Moxico one of the most contaminated of all the provinces. It was one of these landmines that Minga had mistaken for a toy in 2009, and each year Angolan’s are killed or maimed by these hidden weapons.

Landmines are indiscriminate. Often designed to maim, not kill; some are made to remove genitals, others to explode in the air spreading shrapnel; they can be filled with ball bearings and are now often made of plastic to avoid detection. Despite the 1997 Ottawa Treaty banning their use and production, their ease of manufacture, the opening of stockpiles (for example in Libya) and the use of IED’s (improvised explosive devices) by terrorist groups and insurgents, has worryingly seen an increase in their use in recent years. But it is the legacy landmines that are the greatest challenge – countries such as Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Colombia, Afghanistan are contaminated by millions of landmines and UXO’s (unexploded ordinance) from past wars. In some of these countries, civilians are dying from landmines that were planted nearly 50 years ago.

Sadly it seems the longer ago the conflict, the harder it is to get the funding needed to deal with its legacy. It’s shocking to say, but when it comes to humanitarian aid and redevelopment, there are often trends; and countries getting the bulk of media interest tend to get the bulk of funding. A country such as Angola, and its largely forgotten war, struggles to get the funding needed to deal with its legacy.

And its not just landmines that pose a hidden threat. Angola is also littered with tens of thousands of UXO’s from the war. Grenades, bullets, rockets, bombs; despite often being decades old and often buried under the surface, the remnants of war are as deadly as when they were manufactured, as fourteen year old Sapalo discovered in an accident that was to change his life.

Sapalo was playing in his uncle’s house when he saw a large rat dash across the room. He looked for something to hit it with, grabbing a lump of rusting metal that was sat on the table. He threw it at the rat.

A bright heat engulfed him and Sapalo was thrown to the floor. Disorientated he tried to get up, but he couldn’t. Unknown to him, that lump of metal he’d picked up had been the explosive warhead from an RPG (Rocket Propelled Grenade). His uncle had found it when working in the fields that day and brought it home in a plastic bag. He’d planned to get it identified, but for now had left it on the table. Its blast had destroyed both of Sapalo’s legs. Later that day they would be amputated just below the knee.

Lying in Luena’s central hospital Sapalo struggles to deal with the pain. His father washes his head in the hope the water might cool his fever. The hospital is desperately under-funded, even blood for a transfusion must be bought by the family, and for Sapalo’s father it’s a constant battle to find the money to keep his son alive.

And the future for Sapalo is bleak. Like most in the area, the family survives as subsistence farmers, they have little surplus from that to sell. Without support Sapalo will struggle to attend school, and even if he manages to get prosthesis, he won’t be able to work in the fields. And with Angola’s economy struggling, the reality is Sapalo may not even get prosthesis, leaving him wheelchair bound.

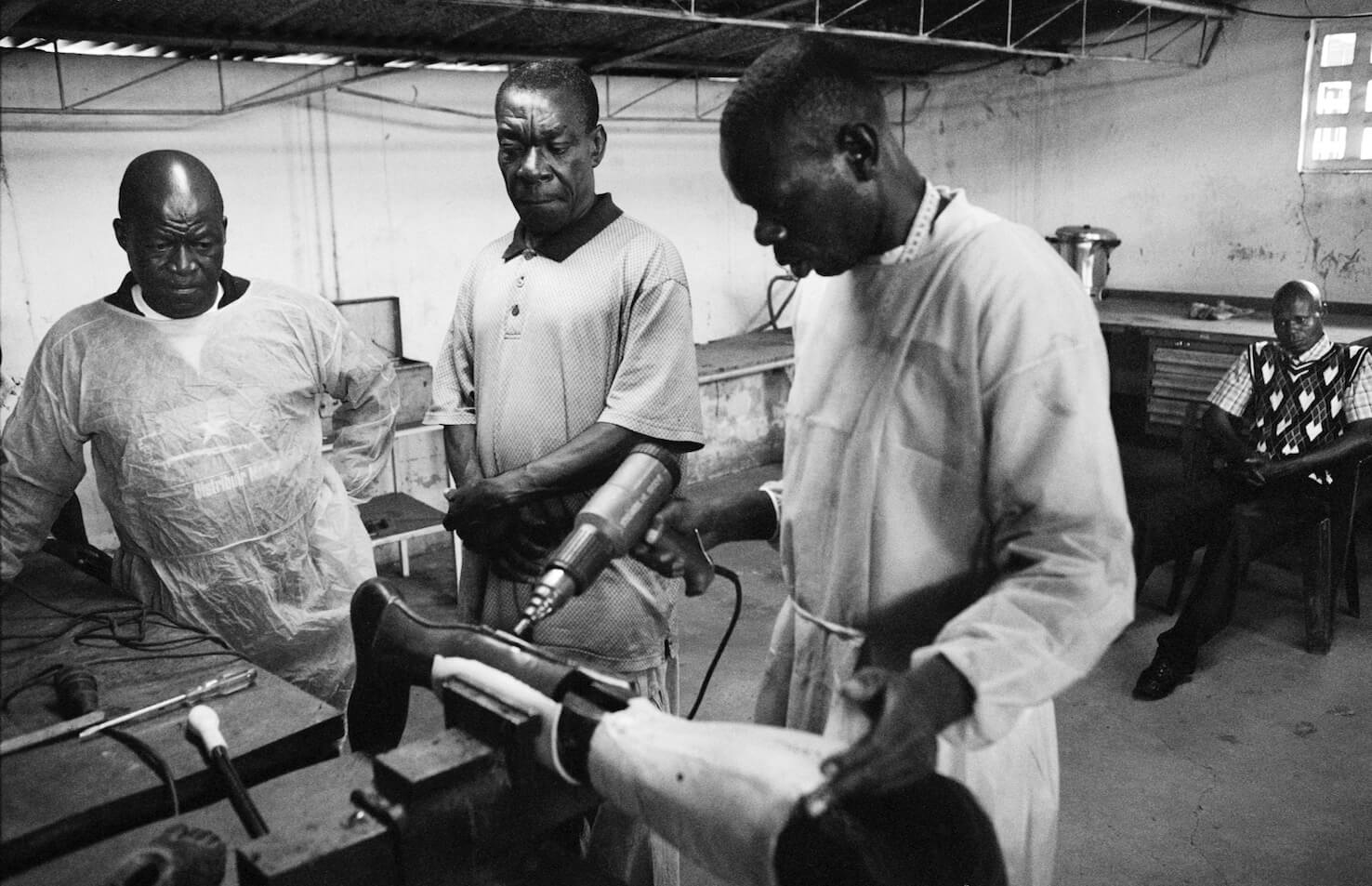

At Luena’s prosthetics centre, where if the funds were available, Saplao would be treated, the staff struggle to meet the huge demand. Each day they arrive promptly at 7am, with clean white overcoats, they unlock the centre, arrange their scant remaining tools on the tired worktop, then sit and wait. The shelves that were once full of materials and newly made prosthesis are bare, and what equipment they have left is held together by tape and the determination of the technicians. Few patients now visit the centre, and those that do are often turned away.

In 2012 the centre was making 150 prosthesis a month. In 2017, that figure was zero. The reality is that they have no budget for materials, the wiring is unusable and what fabrication machines they had are long since broken. Many of the staff has not been paid for years. Yet still each day they go to work and perform a routine of normality and try to do as best they can.

A young man arrives with a prosthesis that has a large crack down the back. Jean Baptiste, the senior technician, holds the broken leg in his arms. For three years, he’s received no salary, yet his dedication to his work is undiminished. But like all the staff, they are frustrated in not being able to use their skills.

The broken plastic leg is held in a vice, empty drawers are searched until a soldering iron is found. Using its heated point Jean Baptiste tries to melt the plastic with the hot tip, to seal the crack. But the soldering iron is broken and doesn’t get hot enough to do the job. He rolls up its cord neatly and places it back in the drawer. Eventually a hot air gun is borrowed, a metal screwdriver heated over an open flame and somehow the leg is fixed.

Watching these scenes it’s hard to feel positive that Angola’s landmine legacy can ever be solved and that survivors will get the chance to live full lives. When it comes to fighting wars, it seems we have no problem funding them. At the height of the Angolan war funds, arms and direct military support flooded into the country from Cuba, South Africa, the United States and Russia, amongst others. Yet when it comes to cleaning up the legacy of that war, the international community needs to do more.

But there is hope. And throughout the country there are NGO’s who have shown a dogged perseverance to clear the landmine legacy despite the challenges. Organisations such as MAG (Mines Advisory Group), who have been operating in Moxico Province since 1994. In 2017, MAG gave back 56 million square metres of land to communities in the province, removing 1800 landmines and UXO items, and helping an estimated 90,000 people.

Mine clearance is a slow, dangerous and exacting job. The technology has hardly changed since the first metal detectors were used during World War Two. Essentially a field is split into grids, and then teams with metal detectors meticulously comb each square. Any anomalies are noted and the ground around then worked away to find their cause. Each piece of hidden scrap metal has to be treated as if it could be an unexploded bomb or landmine. In the fierce Angolan heat, keeping your focus and attention for such long tedious hours pushes the teams to their limit. But for them its not a job, they are making safe the land of their own country.

Watching mine clearance in progress brings home how slow and labour intensive the work is, but also illustrates that this issue is solvable, it simply comes down to funding. If the number of teams working could be multiplied then Angola could become landmine free. But the opposite is happening, in the last ten years international funding for mine action in Angola dropped by $25.9 million, and in the last decade the funding has dropped by a staggering 90%.

The goal is for all of Angola to be landmine-free by 2025, but at least $34 million in funding is needed every year to make that happen. To clear Moxico province in that timescale MAG needs $8 million per year. But, without an increase in commitment from the international community, theses goals are in doubt.

______________________________________________________

Minga is a fiercely determined fifteen-year-old. Despite losing her sight she tries to do everything as she did before the accident. Her week is spent in Luena where she goes to school, but she is happiest when she returns to the family’s small village in the country. There she pounds cassava, helps to cook and still walks for an hour down to the bridge where she was injured, to wash her clothes in the river.

What does she hope for the future? To be a teacher. Her dream is to help other children who’ve lost their sight like her and to teach them braille. As skill that has changed her life

Her resilience is inspiring, but she should never have had to go through this. Resilience, an attribute born through suffering, is not a quality a young girl should have had to rely on.

Just a few miles from the bridge where Minga was injured an old metal door rests against a tree. It’s been there since 2002, a relic from the day the UNITA leader Savimbi was killed, when the door used as a makeshift stretcher. In many ways this is the spot where the war ended. But in Angola you see clearly how a war doesn’t end when a peace treaty is signed, it’s legacy is still leading to death and injury.

And until the funding for mine clearance is increased, children like Minga and Sapalo will continue to pay a heavy price for a conflict that was supposedly over before they were even born.

To find out more and support MAG’s vital work:

OTHER STORIES