South Sudan – Three Minutes, One Call

Akobo, South Sudan

September 2015

Three minutes, one call. To whom? What would you say?

Hundreds of thousands of men, women and children have been displaced or have fled into neighbouring countries following the crisis that erupted in South Sudan in December 2013. Staying in contact with family and friends keeps hope alive, but time and opportunity are invariably short.

To help people find and keep in touch with loved ones, the Red Cross has expanded its ‘Restoring family links’ (RFL) activities in the country. The service includes free phone calls, hand-written Red Cross messages for conveying family news, and a photo album of displaced South Sudanese allowing people to identify their relatives.

We live in the most connected of times. It has never been easier to communicate with a loved one – by text, email, Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, Skype or simply by phoning them. Friends, colleagues, family members are all available to us 24 hours a day no matter where they are in the globe. This is the era of communication.

So imagine if that was all taken away from us overnight. What if instead of mass communication you could phone just one person, and for only three minutes. Who would you call? What would you say?

For many people in South Sudan, this is their reality. In 2013, just two years after it became an independent state, South Sudan was thrown into a brutal civil war. Communities were split and families separated. In a bid to disrupt communications, the already strained mobile phone networks were destroyed, silencing the only form of communication people had with their loved ones.

Akobo is a town in Jonglei State, on the border with Ethiopia, about 280 miles from the South Sudanese capital, Juba. It had suffered through years of war, so in 2011, when South Sudan finally became an independent country, a wave of optimism swept through the town. Finally it seemed peace had come and many from Akobo moved to Juba to look for new opportunities to work or study.

In Akobo itself, many families were split as men stayed to look after their homes and farmland while their wives and children sought refuge from the fighting in neighbouring Ethiopia and Kenya. Most thought the war would be over in a few weeks and that families would be reunited.

Then the phone networks were shut down and Akobo, like many towns and villages in South Sudan, found itself shut off from the outside world. As the war raged on, the means of contacting family and friends was lost. Many were unsure if their loved ones were even alive. In this connected world, Akobo had lost all communication.

Then, in 2013, the ICRC’s RFL programme came to Akobo. As part of the project, in July 2014, people had the chance to use a satellite phone. For many this would be the first time they had spoken to missing relatives for two years.

Sheltering from the savage sun under a tree on the outskirts of town, Akobo residents sit waiting patiently for their turn on the phone. They register, as many as 200 a day, then wait. When the loudspeaker calls their name, they walk forward, clutching a piece of paper with the precious number. They hand it to the ICRC staff member, who dials and then passes the phone back.

They are allowed just three minutes.

It’s hard to imagine, but for the residents of Akobo those three minutes are their lifeline to the world. If you had those three precious minutes to speak to the person you loved. Who would you call? What would you say?

© Giles Duley / ICRC

Nyanchan was calling her sister. She was in an internally displaced persons camp in Juba. They hadn’t been in contact since 2013. She wanted to tell her sister they had found another relative in Juba and hoped to put them in contact with each other so that her sister would not be alone.

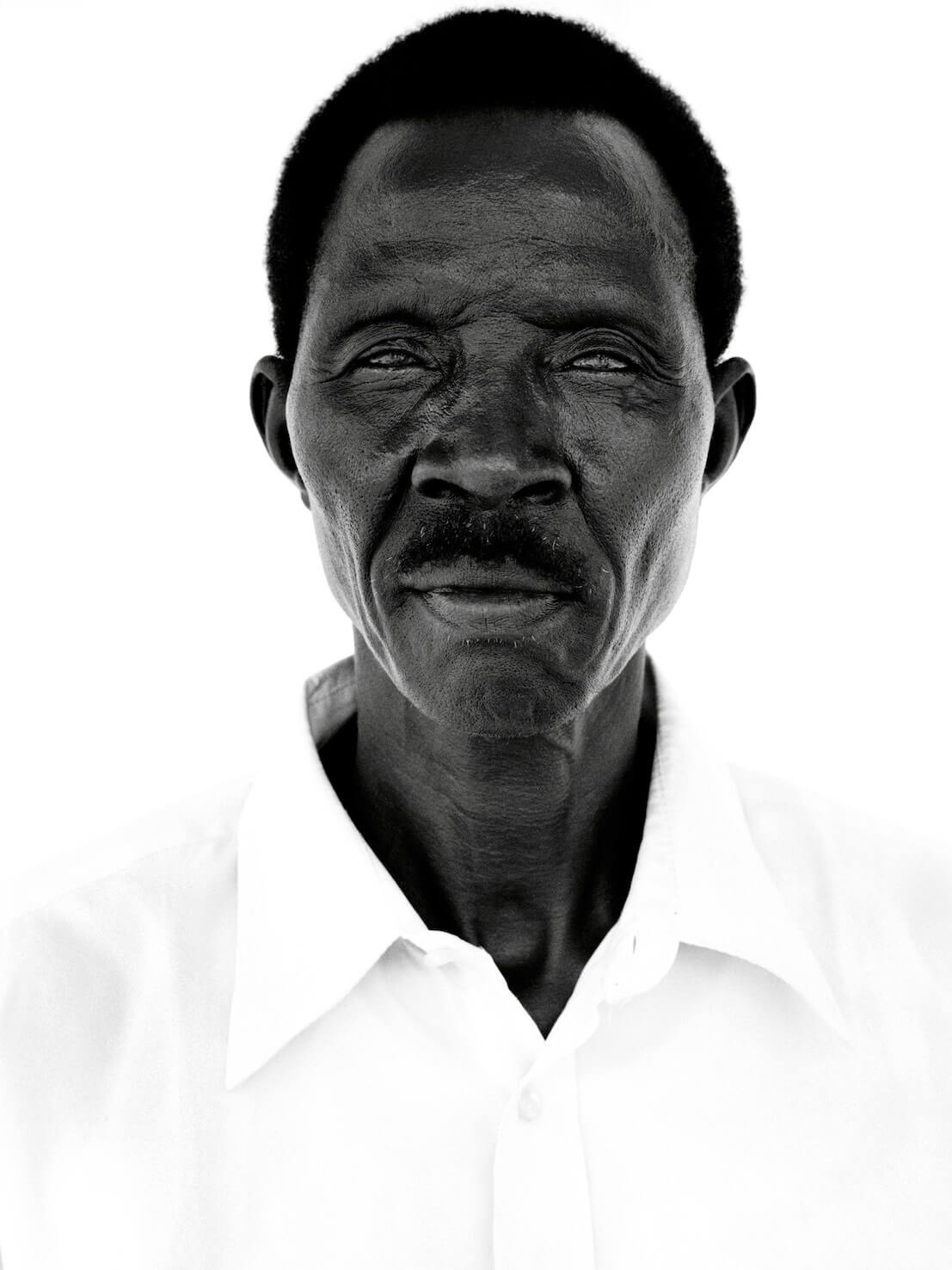

Liep was calling his wife, whom he hadn’t seen or spoken to since December 2013. He wanted to know how she was and to ask about his children. Liep wanted to say: “I miss you and our children, but don’t worry, I’m doing well.”

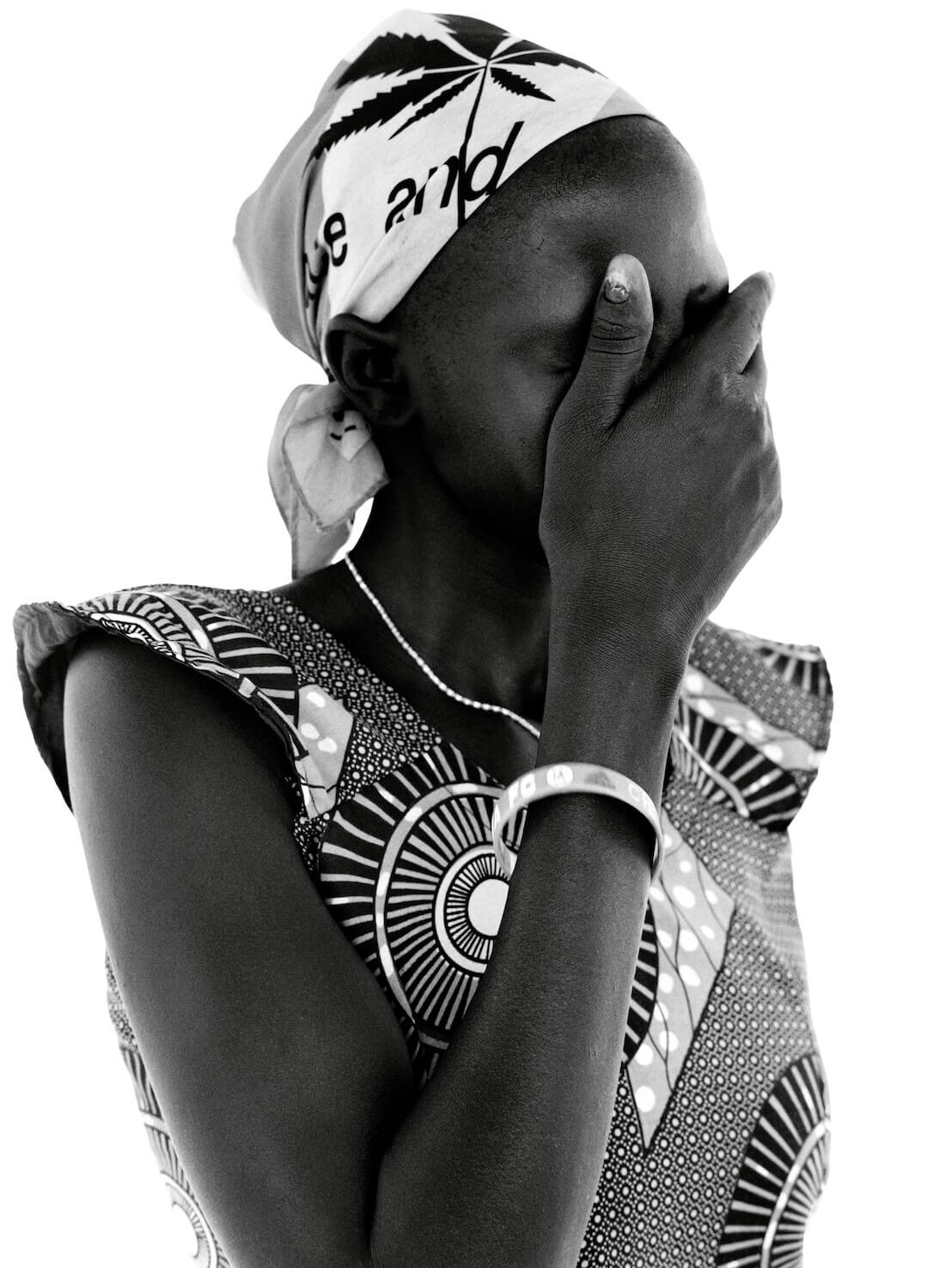

Nyabouth was trying to contact her husband, who she last saw in July 2015. She wanted to tell him that their child was due in the next few weeks, but not to worry. “Everything here is ok.”

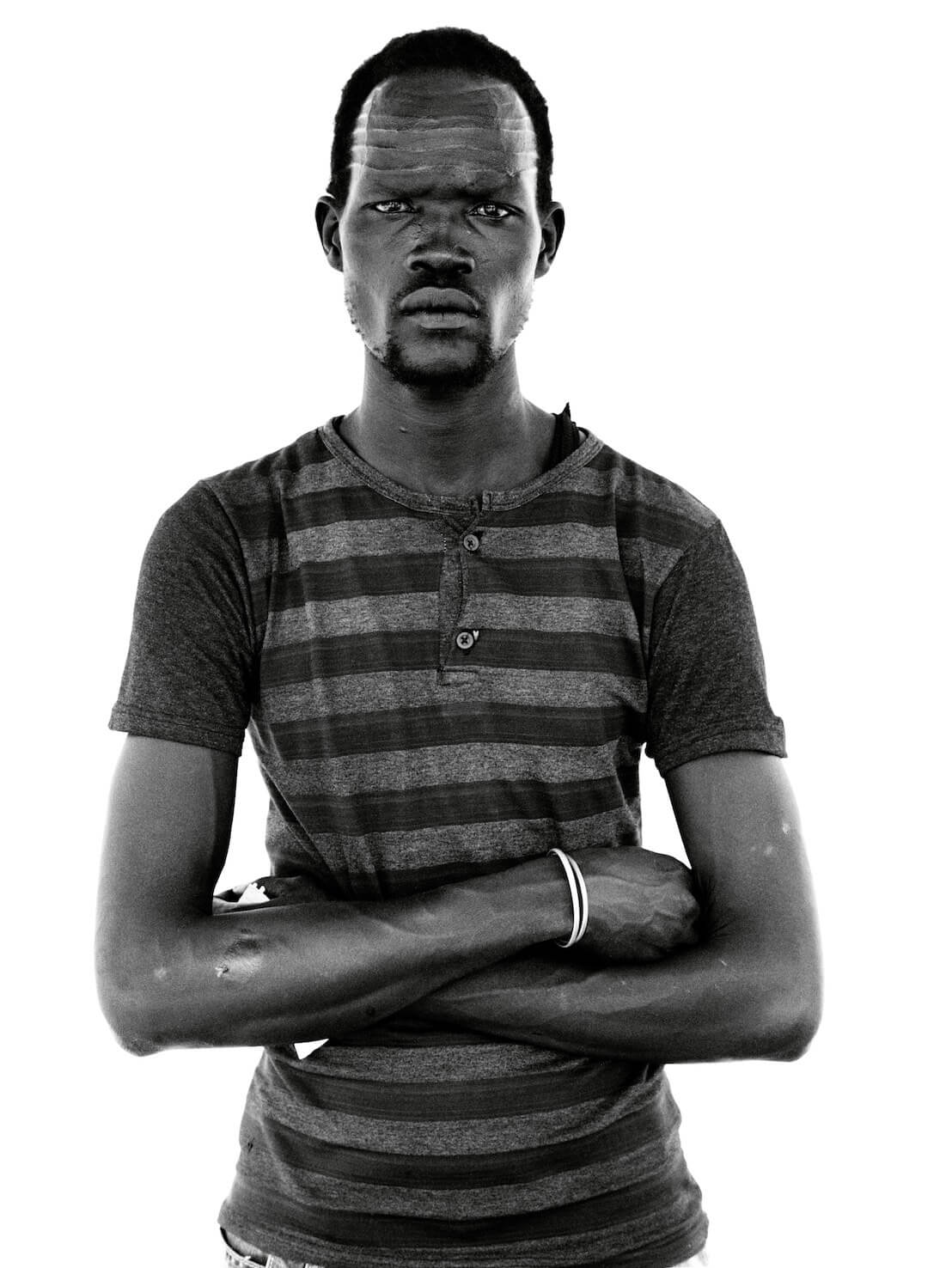

Panum was trying to make contact with his brother, Yen, who he hadn’t heard from since the Civil War started in 2013. He’d gone to Juba to study, and Panum thinks he found refugee in a UN compound when the war started, but he can’t be sure. Panum lives alone with his mother, his father was killed in recent fighting. He’s desperate to find his brother, in the hope he can help them, as they are struggling to survive. He walked for three hours from Nyandit Payam village to try and call his brother. There was no answer.

Nyiakubo was calling her brother whom she thought had been killed in the fighting. She hadn’t heard from him since 2013. During the call she started to cry. “I am crying because I thought that my brother had been killed, but now I hear his voice. I’m so happy,” she said.

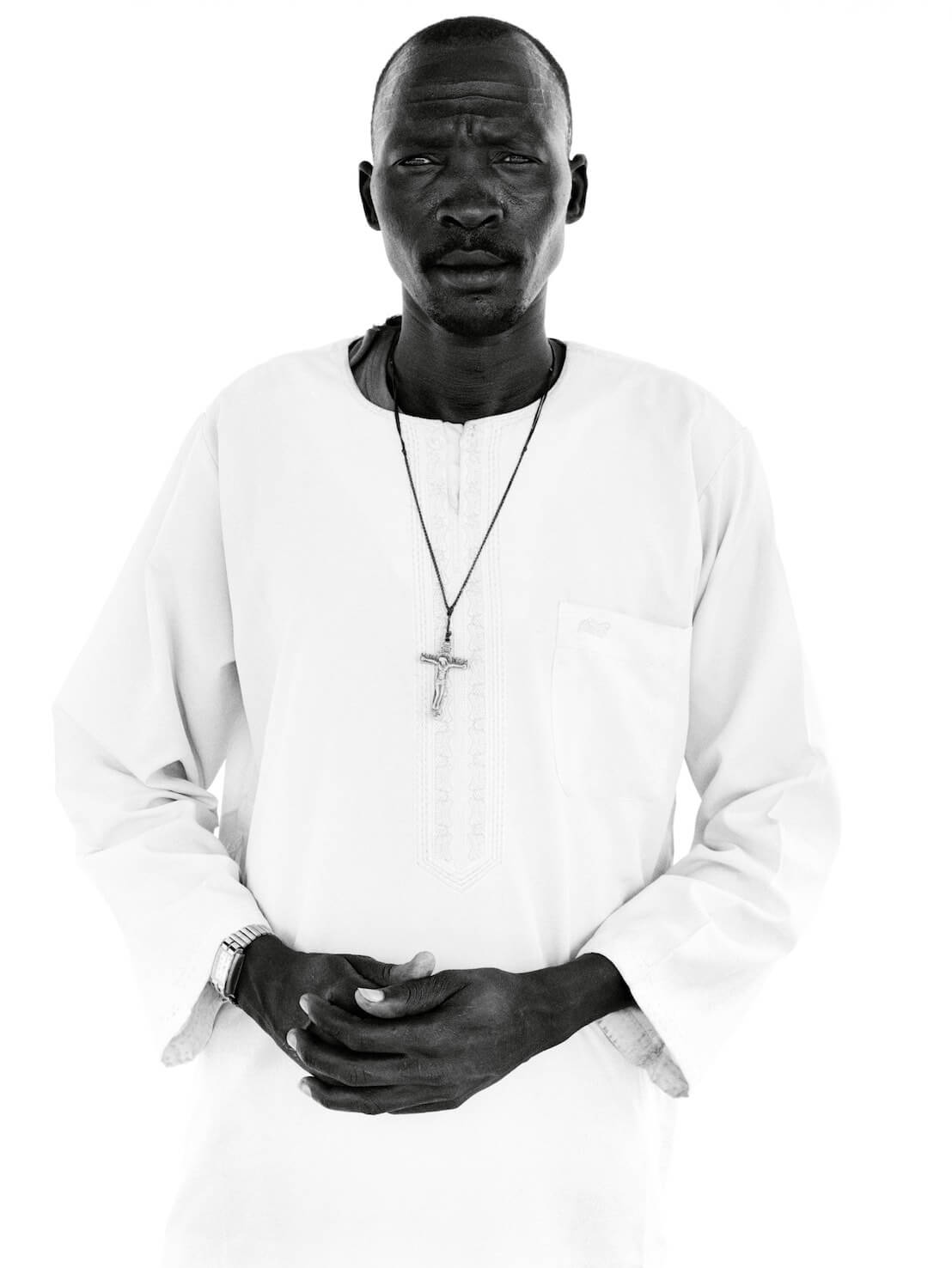

Chol was calling her daughter and son-in-law, with whom she had lost contact in December 2013. They were now living in Khartoum, Sudan. When the war started, Chol was left alone and she has nobody to help her. She asked her family to send clothes and money. “Because of the war I have nobody,” she said.

OTHER STORIES