Syrian refugees: ‘We want to go home. That is our dream’

Lebanon

October 2014

Sometimes the photographs you don’t take, are as important as those you create. I’ve just been introduced to Aya, who sits in front of me on a concrete floor, small and lost, and although I’m here to photograph her, it feels like the wrong thing to do. As far as possible in my work I try and see the people beyond their injuries, illness or situation; to respect them as the individual they are. This time, I’m struggling to do that. Aya is four years-old, has Spina Bifida and is homeless.

_____________________________________________________________

I came to Lebanon with the charity Handicap International to document the lives of some of Syria’s most vulnerable refugees; most especially people with disabilities, many of whom are going without essential needs. It has been a difficult and harrowing trip; I’ve met many refugees throughout my career, but here I am hearing some of the worst stories I can remember.

The statistics of the Syrian refugee crisis are hard to comprehend. Over three million Syrians have now fled the country, with Lebanon alone taking in nearly one and a half million. In this small country of just four million, that equates to the population growing by 25% in just a few years. And that number is increasingly daily.

In Lebanon, refugees are faced with unique problems. The government is yet to allow the UNHCR to build an official refuge camp. As a result those fleeing to the country are forced to rent whatever space they can, from substandard flats, to garages, and even cowsheds.

Not all though can afford rent; many are left to build their own shelter on whatever ground they can find. There are now over 1600 Informal Tented Settlements (ITS) dotted across the country, making the distribution of support a logistical nightmare.

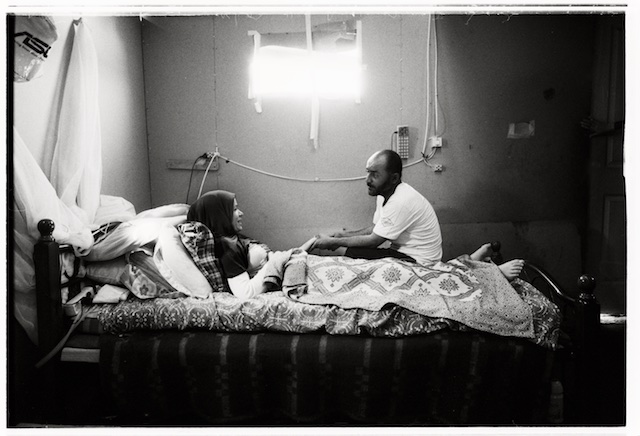

Khouloud lives in a makeshift tent at an ITS in the Bekaa valley, just a few miles from the Syrian border. The tents here are made from whatever materials the refugees can find; tarpaulin, cardboard, even posters advertising Hollywood blockbusters, ripped down from billboards. Inside the air is stale, the heat oppressive. Khouloud lies on her bed, her husband sits next to her, holding her hand. She was hit by a sniper’s bullet in the back, leaving her paralysed from the neck down.

“I had tried to plant a small area of land near our house as it wasn’t possible to get vegetables like before,” she explains, “I was going to take care of the plants with my four children and suddenly a bullet hit my neck and I fell down and lost sensation. I could not move any more. The children started shouting and yelling.”

The doctors gave her just a one percent chance of survival, but she did. Soon after, she and her family left Syria because the hospitals, which are overwhelmed with war wounded and lacking supplies, couldn’t offer her medication or physiotherapy. They’ve been living in this tent for five months.

The UNHCR provides food coupons, but the family is struggling. Khouloud’s husband now has to provide her with twenty-four care. As we talk, he gently strokes her hand.

I ask her what hopes she has for the future, she replies simply; to be a mother again.

“I need a miracle to happen”, she says, “I wish I could move my fingers because sometimes my son is injured outside and he comes in next to me. He moves my hand and he puts my fingers onto the wound. I wish I could move my fingers to touch the wound and make him feel like I am feeling it with him.”

Khouloud was shot by a sniper, leaving her paralysed from the neck down. She now lives with her four children and husband (pictured), who provides her care, in a makeshift tent in the Bekaa Valley.

Nearby lives Reem, 38, she fled here from Idlib two years ago, after her house was bombed. Her husband and daughter were killed, and Reem lost her leg. Initially she was overcome by what had happened; her hair fell out, she suffered from anxiety and depression. Her other three children went to live somewhere else; she didn’t want them to see her.

However in the end, it was those children that gave her focus. One day she said to her Handicap International physiotherapist Abeer, “I want a prosthesis very fast because I want to see my kids. I don’t want to let them see my amputation. I don’t want to show them that I can’t help them and I can’t do things well in front of them.”

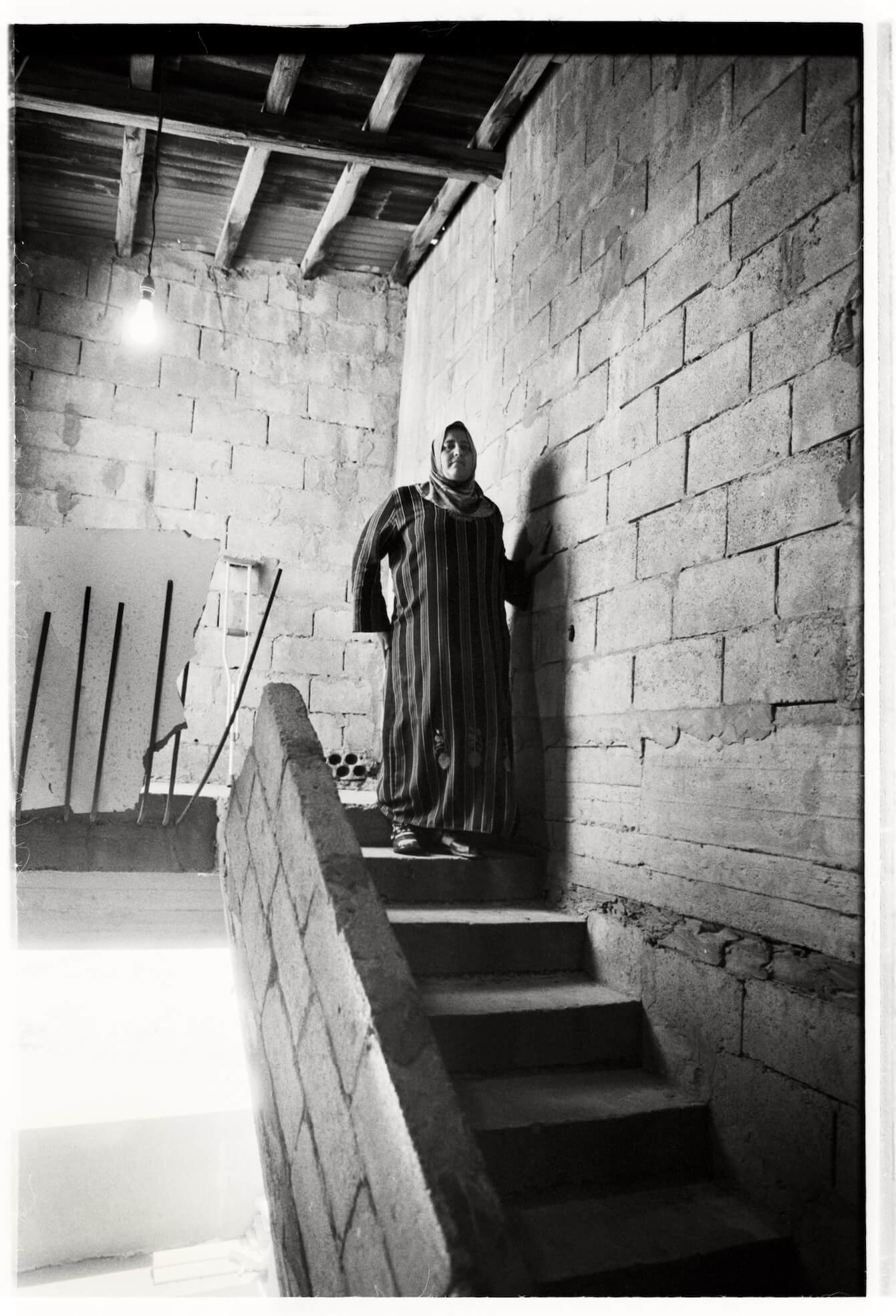

HI was able to provide a prosthetic leg and from that moment, Abeer says she was incredibly driven and now she has been reunited with her children.

Reem’s story is hard to hear and she can still hardly talk about what happened. However what shocks me is where she lives. With few options her and her family were forced to live in a tent on the rooftop of an unfinished three-story building. I struggle to climb the bare, unsupported concrete stairs to the rooftop, exposed metal poles protruding around me. For Reem the task is too much; she can only manage a few steps. She is stranded on the rooftop. It has become her prison.

Reem lost a leg when her house was bombed, killing her husband and daughter. Now she lives on the roof of a half-built house in Bekaa. Until she learns to use her prosthesis, she is trapped at the top of the stairs.

For many though, even finding proper shelter isn’t the end of their nightmare. I visit Noor in the tiny apartment where she lives, on the sixth floor of a building in Tripoli. Like all the Syrians I meet, her hospitality comes first; seeing I’m exhausted from the stairs and heat, she gets me a chair and cool water. Sat opposite me, Noor cradles her daughter Iman, the two of them look like they haven’t slept for weeks, dark circles shroud their eyes. It seems as if all life has gone from them. On a sofa her ten-year-old son Khalil tries to shift his position, but winces in pain as he does so. Noor reaches forward to stroke his hair.

Just over a year ago a bomb hit the building where they were living and Khalil was thrown from the third floor. As a result his hip was shattered, so the family left for Lebanon. After six months Noor’s husband returned to Syria to help his sick mother. She never heard from him again, one of Syria’s many disappeared. It’s estimated in Lebanon and Jordan there are now over 70,000 female-headed households.

On her own, with four children to support, the situation became increasingly desperate. Khalil was bed-bound and in desperate need of an operation, but she was told he that it would cost $8000, far more than she could ever afford. As a result his hip is deteriorating due to osteonecrosis leaving him in great pain. With no income, they were no longer able to pay rent and they found themselves living on the street. Eventually a man took them in and let them live in the apartment where they now are.

As she tells me her story, I sense that there is something terribly wrong in this situation. Wassila and Abdullah, the Handicap International team I’m with, confirm my fears. They are desperate to find her protective housing, but as of yet they can’t find anywhere that can take her. Wassila looks at me, “the man that she is living with is not good to her.”

With Khalil’s hip deteriorating and with no way of making an income, Noor has few options. As we leave she calls down the stairs, “Abdullah, please don’t forget me!”

“Don’t worry, it’s ok”, he calls back, but as his words echo up the stairwell, they seem somehow empty. Things here are so far from ok.

Noor cradles her daughter, Iman. Her son, Khalil, is bedbound, in need of an operation on his shattered hip that she can’t afford. Her husband is missing in Syria and, unable to pay rent, she was left homeless in Tripoli.

Handicap International is one of many charities helping the Syrian refugees, but as the only charity solely dedicated to supporting people with disabilities, they see many of the worst cases. When visiting with the teams, I’m taken by their incredible dedication and professionalism, but they seem tired, worn-down with the relentless nature of this crisis. The simple fact is that all the charities are stretched, their staff pushed to breaking point.

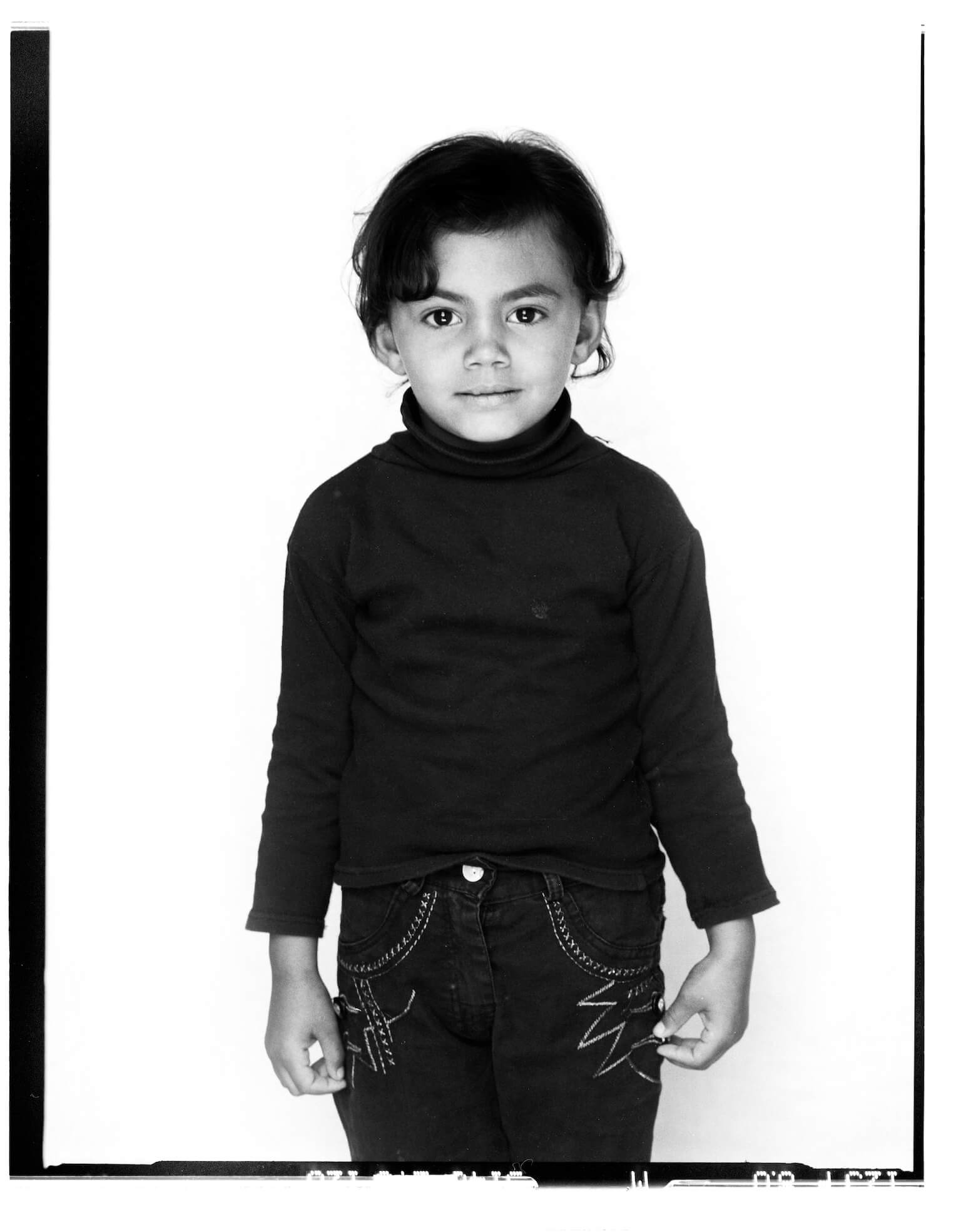

And it’s not just the physical injuries of the Syrian war that the charities are having to deal with, there are hidden wounds. Bana was four years-old when she was shot in the chest. It was an accident, a five year-old boy discovered a gun and whilst playing, it went off. In Syria, weapons have become commonplace and children are exposed to constant violence.

Bana was taken to a small clinic where there were no medication or bandages. They operated on her without anaesthetic. Around were bodies of those injured and killed in recent bombings. She was left traumatised. When she saw the bodies in the clinic she was shouting at everyone she knew, “Go, go, go! Get out of here now, you will die in this place!”

Bana’s house was bombed, she was accidentally shot by a neighbour’s child, and was so traumatised by the many dead she saw that she stopped talking and eating, and refused to leave her mother’s side.

By the time she returned home, she had retreated into herself. As her mother explained, “She stopped talking. Bana wasn’t eating, she was aggressive, she was beating her older brother and sister. She was afraid to go out, to open the door, she was always afraid. Also she refused to walk. She always wanted me to carry her. She wasn’t sleeping very well, she had nightmares and would wake up suddenly.”

The UNHCR offered to get Bana and her family out of Syria, but before they could, a bomb hit their house. Bana was injured again, as were her sister and mother. They fled immediately for the border.

Now in Lebanon and with the help of HI’s psychologists, Bana is slowly recovering. It’s a long and painful process though; she’s still constantly afraid, shouts every time she hears a plane and still refuses to leave her mother. In some ways though she is a lucky one. Nobody knows how many children are suffering from trauma caused by the war in Syria, but it’s in the tens of thousands and most are receiving no treatment.

According to Save the Children, four out of five Syrian children in Lebanon lack schooling. For some it has now been years since they had any education. Combined with the violence they’ve witnessed, and the constant fear they experience, charities are now referring to a Lost Generation of Syrian children. Yet this will be the generation expected to rebuild a shattered country when peace does return.

It’s so easy just to class people as refugees, and then say, “I don’t understand them. I don’t know what they are like.” But in these camps I don’t find refugees: I find taxi drivers, mechanics, teachers, doctors, lawyers; I find mothers and fathers, children and grandparents; I find the same hopes and fears that are expressed in households across the world, “my child educated, my loved ones healed, my family safe”. And when I ask what is your dream? It’s always the same, “To go home. To go home.”

Yet with peace looking further away than ever, it seems this there will not be possible anytime soon. With the region preparing itself for even more bombing and an intensification of fighting, this crisis is going to get worse. We have to find ways to protect these civilians who have been forced to flee their homes and lives. At the moment they are stuck in an impossible limbo.

At the beginning of the crisis, there was a clear lack of strategy by the Lebanese government. Many didn’t believe the problem would be a long one and certainly not of the scale it became. Camps were not built, ostensibly for historical and political reasons. Whether an ‘official’ camp would have been the answer is open to debate, however it would have made the NGO’s work more centralised and permanent.

The sheer number of Syrians arriving in the country would be impossible for any country’s infrastructure to cope with. Lebanon’s was already in need of support, its now being overwhelmed. Water, sanitation, electricity, accommodation, schools, hospitals; none of them are able to cope with the 25% increased demand refugees are creating.

As the central organisation dealing with refugees, it’s easy to point the finger at the UNHCR for some of the failings. Its true, in some cases it doesn’t seem to be meeting its own targets, however it has only received 30% of the funding it’s asked for, and which it sees as vital to even operate on an emergency level. Without that funding it simply can’t do all its needs to. As one representative from the Red Cross said to me, “It’s easy to blame the UNHCR, but I’d like to see anybody do a better job.”

And it’s not just the UNHCR that is struggling with funding. Most of the charities operating in the region are struggling to reach even 50% of their funding targets, meaning at a time when the refugee numbers are growing, many essential projects are being cut back. Housing, medical support, education, specialist care for disabled people, vulnerable women and the elderly; all are under threat. It’s not that the charities aren’t doing enough, it’s that there is simply too much for them to do, with far too little money.

So what has to be done to stem the risk of Lebanon’s collapse and to safeguard the wellbeing of the most vulnerable refugees? Most agree that there needs to be a clear vision, a vision that moves on from temporary solutions and looks on this as what it is; a long term issue. Secondly there needs to be far more support from the rest of the world. Donors have to be found that can bridge the gulf in funding.

However if you ask the refugees or the NGO’s, what do you think is the best way to deal with this crisis? They will all give you the same clear answer.

“How do you end the refugee crisis in Lebanon? Simple, we need to find peace in Syria.”

_____________________________________________________________

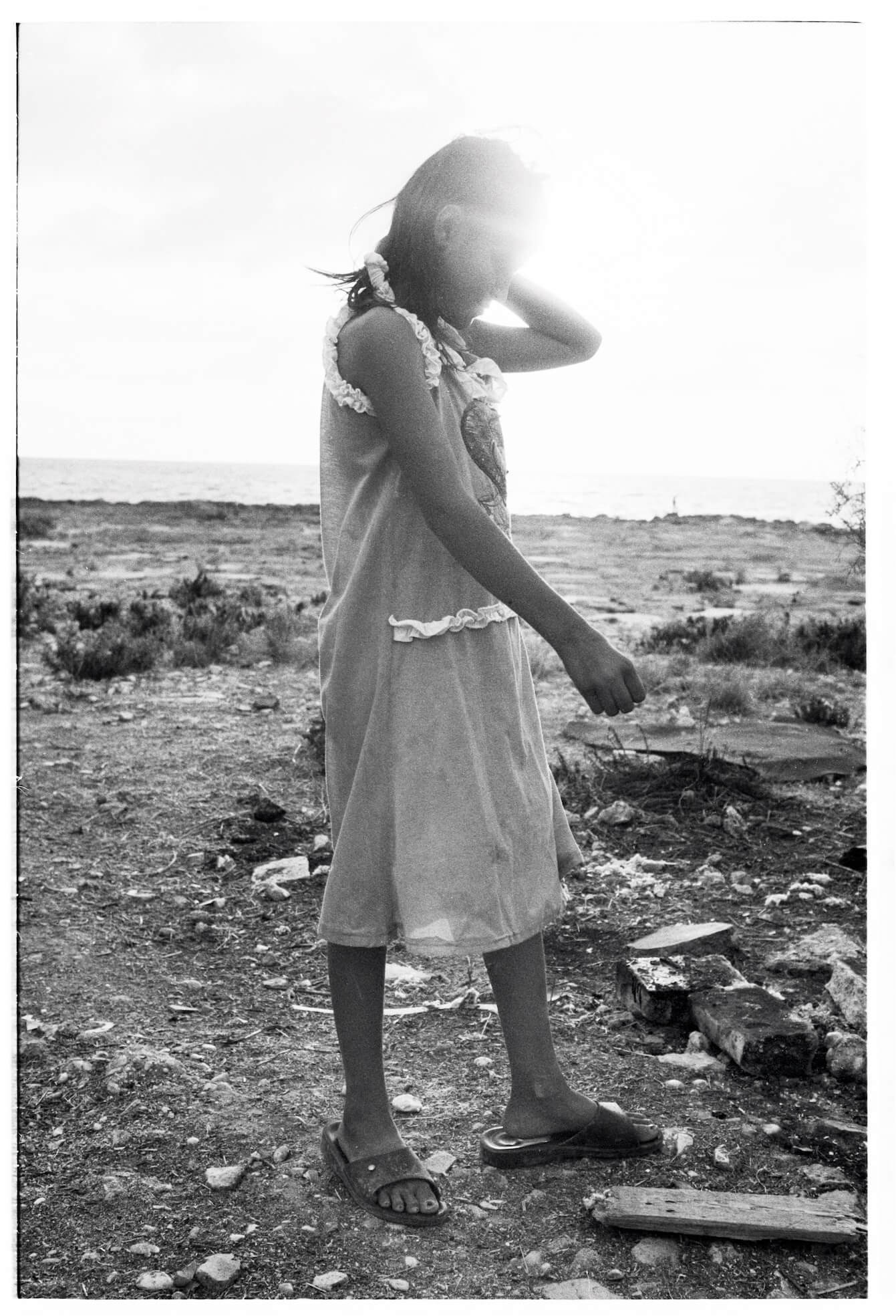

Aya’s lives in a small makeshift camp by the sea, a few miles from Tripoli, with her two sisters, two brothers and parents. A handful of refugees have settled here, on wasteland by a cement factory. There is little protection from the elements, the children get sores from insect bites and everyday there is the threat of eviction.

There are no schools for the children to go to, there are no jobs, the hospitals and doctors too expensive. The UNHCR provides Aya’s family with food coupons, but there is no support for accommodation or shelter provided. Each week the family gets further in debt.

Just a few months before, things were very different. The family had their own business in Idlib. Aya’s mother, Sihan, worked as a kindergarten teacher, the kids were doing well at school. Aya’s condition, though bad, was being well monitored, with trips to the doctor every two weeks. They were, according to Sihan, very happy.

Then in March their home was destroyed. For ten days they hid in a basement while the bombing continued. They had no electricity, water or toilet. When the bombing stopped, they escaped and headed to a cousins house in a nearby village. The journey to Lebanon, and relative safety, took a further two months

At this point Sihan stops telling me their story. “It shouldn’t be me telling you this, it is Iman who saved Aya. She should tell you”

“What do you mean?”

“Iman held her all the way from Syria, she carried her.”

Iman is sitting on the floor next to Aya, she’s just nine years old. “You carried her?” I ask

“Yes, I have been carrying her since she was one year old. I can’t hold her like a baby anymore, so I hold her on my hip.

When the war came, there was a store underground. We hid there. I was looking after my sister. All the time we were afraid because we could hear the bombing. I was keeping Aya on my lap all the time, she was so scared.”

“She did everything for her,” Sihan interjects, “she changed her dressings and changed her clothes, she did everything for her. It took us two months to get here and Iman carried her.”

Looking at Iman and Aya, it was hard to imagine that journey. The risks and challenges for anyone fleeing though a war torn country are so great; but with a child in a wheelchair, a paralysed partner or frail grandparent those challenges become that much harder..

Likewise being a carer is difficult and often overwhelming in the best of situations. However, trying to provide twenty-four care for somebody with a disability in a makeshift tent, with no running water, sanitation or easy access to medical care must be near impossible. Yet many are having to do just that.

Later that day, as the sun drops and the temperatures become bearable, the children go out to play. As always, Iman is carrying Aya. As I’ve spent more time with the family I’ve started to see Aya’s incredibly fiesty nature and positivity. She is so full of life and you can see that reflected in the happiness she brings those around her, despite their terrible circumstance.

As they start a game of hopscotch with the other children, Aya screams with laughter and I finally see the photograph I’ve been searching for.

Raising my camera I shoot a few frames and I’m done. Walking over to Aya, who’s now sat in her wheelchair, I ask her “you must love your sister very much?”

She pulls a funny, quizzical face, then smiles as she stretches out her arms as wide as she can.

“This much” she says, “I love her as much as the sea.”

OTHER STORIES