The children of Gaza who live with the legacy of war

Gaza

May 2015

Farah takes his daughter, Maryam for a walk. Fom the moment of her birth, Maryam’s life has been shaped by conflict. War is something her family are desperate to escape from, but with restrictions on movement, they are trapped.

For the past six months I have been travelling, recording stories for Legacy of War, a two-year project documenting the long-term impact of conflict on communities and individuals around the world. Lebanon, Jordan, Northern Ireland, The States, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos; to name just a few, with many more to come.

My work is not focused on the histories of war, the facts and figures; the political rhetoric and diatribes that fuel them; the divides, fears or greed that start them. Those are important in understanding the causes, but my interests lie in the consequences and legacies. The commonalities that often scar those who’ve lived through conflict.

For five-years I worked as a carer for children with autism and so for a long-time I’ve been interested in seeing how those who see the world differently cope with the incredible challenges of living in a conflict zone. The collapse of routine, loss of familiar settings and the death of loved ones sadly become common events in war, causing many children to suffer from mental health issues; for those with heightened sensitivities the effects could be far more acute.

Which is why I went to Gaza. There are few places that have seen more conflict in recent years and the resulting physiological impact on the civilian population has been well recorded. Especially on the young.

In Gaza, as well as the estimated 3000 children with autism, there are many others with learning disabilities and mental health issues. Not only are they directly affected by the conflict; the war and on-going embargo has also affected the support network of schools and outreach programmes. This has put extra strain not just on those living with disabilities, but also on their families.

For some, the conflict has shaped them before they are even born.

_______________________________________________________

On 21st November 2006, as Asma and her family sheltered together in a downstairs room of their house, they listened to the now familiar sounds of fighting around them. The family lived near Beit Lahiya, a small town in Gaza, just a few miles from the Israeli border; a proximity that meant their home was always in the frontline when war broke out. Throughout that summer, their house had been in the middle of some of the fiercest fighting between the IDF and Hamas. Now, after a period of relative calm, Israeli troops had once more crossed the border and fighting had resumed.

The day before the IDF had entered Asma’s home, occupying it and forcing the family into a single room. Israeli snipers had taken up positions on the roof, meaning Hamas was now targeting them with rocket-propelled grenades. There was nothing the family could do, but huddle together and wait, but for Asma it was particularly stressful, she was seven months pregnant.

As the family listened to the blasts of gunfire and rockets outside, they heard a different noise. It was the sound of somebody knocking, and the voice of an elderly woman calling their name, asking to be let in. The family, confused and fearful of moving, stayed put. They heard Israeli voices shouting from the roof, a small explosion and then the woman’s voice asking once more to be let in.

Before they could reply, a huge blast ripped through the house. Smoke and gasses filled the air; Asma was choking, struggling to breath. She remembers the sense of suffocating, then nothing.

Unbeknownst to the family, the woman outside had been Fatima Omar Mahmud al-Najar, a 64-year-old grandmother and suicide bomber. She had been sent by Hamas’ military wing to kill the snipers on the roof. But before she could carry out her attack, the Israelis had spotted her and threw a stun grenade. So she detonated her vest before she could enter the house, saving the family from the full impact.

However the blast had starved Asma of air and she was struggling to breath, she was rushed to Al Shifa hospital where the decision was made to induce her pregnancy. Maryam was born that evening. For a week she slept in hospital.

When she came home, the family knew something was wrong, but they were unable to get a diagnosis. Maryam would scream constantly, slept for no more than an hour and seemed unresponsive. Then her epileptic fits started. Finally, a year after she was born, Maryam was diagnosed as having severe hypotonic cerebral palsy, caused by the lack of oxygen when she was born.

Asma was told her daughter would never walk, talk or even be able to feed herself. She would need constant care for the rest of her life. Maryam, who was born in the midst of war, would live forever with its legacy.

Visiting Maryam is a difficult experience. She sits in the arms of her grandmother Manzuma, unable to hold up her head or control her limbs, she is like a rag-doll with painfully sad eyes. Her brothers Muhammed and Juma are sat on the floor, bathed in the flickering light of the television, watching Heaven Birds, their favourite channel. With the normal generous hospitality of Palestinians’, Asma prepares coffee and cuts cake in the makeshift kitchen.

The family is living together in one sparsely furnished room, forced there after their house was hit once more during the latest Israeli offensive, Operation Protective Edge. Eight rockets were fired at the house in July of last year; one hit the upstairs floor, setting it on fire, a piece of shrapnel injuring Maryam in the side.

The wound has healed, but her condition has worsened. Farah, Maryam’s father, is explaining to me that since the night of the rocket attack her screaming has grown worse, her crying abnormal.

“She is having more fits since the attack. After the crisis and her last injury, her screaming increased. All the night, she is screaming, she is crying.

Before she was in a much better situation. Before she was moving around a bit, now she doesn’t move at all. She didn’t understand what was going on.”

As I sit there drinking my coffee, I find it hard to imagine what life is like for Maryam. Unable to comprehend the war that goes on around her, it has still shaped her life and continues to do so. Her’s is a desperate situation; the family home nearly destroyed, their income as farmers gone, a lack of psychological or physical support and hardest of all, no escape from the home that they know will be caught in the crossfire when war comes again. Due to the lack of freedom of movement and financial constraints the family has no choice but to stay.

Later, Farah takes me onto the roof to show me where the rockets hit. “The problem,” he says pointing in one direction, “is that when those over there fire on those over there”, his arm swinging to point the opposite way, “then those over there, fire back. We are in the middle.” It’s a simple illustration of the fate of so many families caught in conflicts around the world, though here in Gaza the situation is worse due to the Israeli blockade. There simply is no way to escape.

As a father he goes on to explain, he wants just one thing. To protect his family, to take them somewhere safe, somewhere where Maryam won’t be injured again. But he can’t.

As my photography matures, I find I spend more time with people and take fewer photographs. In a world where speed and efficiency seem valued above all else, I’ve made the conscious effort to slow down. Spending time with people, observing their daily life, sharing food and coffee, watching for small gestures and most importantly listening to their story. Only then does the photography start.

Sitting with Maryam and her family, I’m struggling to find that moment. I can’t see the image that does justice to her story, its not coming to me and I’m fighting my camera.

That day I leave without having taken a single photograph. The evening is spent struggling with how I move forward on this story, to do it justice, to retain the dignity of those I’m photographing.

The next day I visit the offices of Handicap International, a charity that works through local partners to provide support for children with disabilities throughout Gaza, including those with intellectual impairments.

Suha Skeikh is a Palestinian psychologist who has worked with Handicap International and written extensively on how the conflict has affected those with learning disabilities and other disorders such as autism.

“Since the crisis ended we are seeing a lot of problems: eating disorders, lack of sleep, bedwetting, aggression, and uncontrolled behaviour. All the progress we made has gone.

The main source of security for a child is the mother. When the mother or family behave in an erratic way during the war they lose this factor of security. The main reason the child can’t understand is the behaviour of the people around them and the loss of security.

Children with intellectual disabilities are known for having good, strong memories. This makes it very hard for them as they keep recalling the war and the scenes they witnessed.”

With Suha, I go to meet Islam, 14, who lives with her father and sister in Gaza city. When she was one and a half, she fell from the fourth story of her building, sustaining a serious head injury that left her with learning disabilities. She struggled to concentrate at school, was aggressive and suffered from panic attacks. Eventually her headmaster excluded her from school and she spent many months shut at home where her sense of isolation and anxiety grew.

Finally, when she was 11, Islam was enrolled in a specialised school and started seeing Suha for psychological support. “The reason for the psychological sessions was the increased anxiety she was facing because she had difficulty communicating with people and was used to staying at home, so school was a strange environment. She was very aggressive and could hit people, so we were trying to work with her and include her in the community.“

Working with Islam’s mother as well, Suha could see the progress she was making. Then on 21st July 2014 as the war intensified, a shell hit Islam’s house. She was hit in the leg with shrapnel, but survived. However four siblings, her grandmother and mother didn’t. She saw their bodies all around her. The psychological trauma on Islam was immense.

“I was not able to reach Islam until the war was over,” recalls Suha, “she couldn’t speak properly, she developed a speech impediment as a result of the trauma.

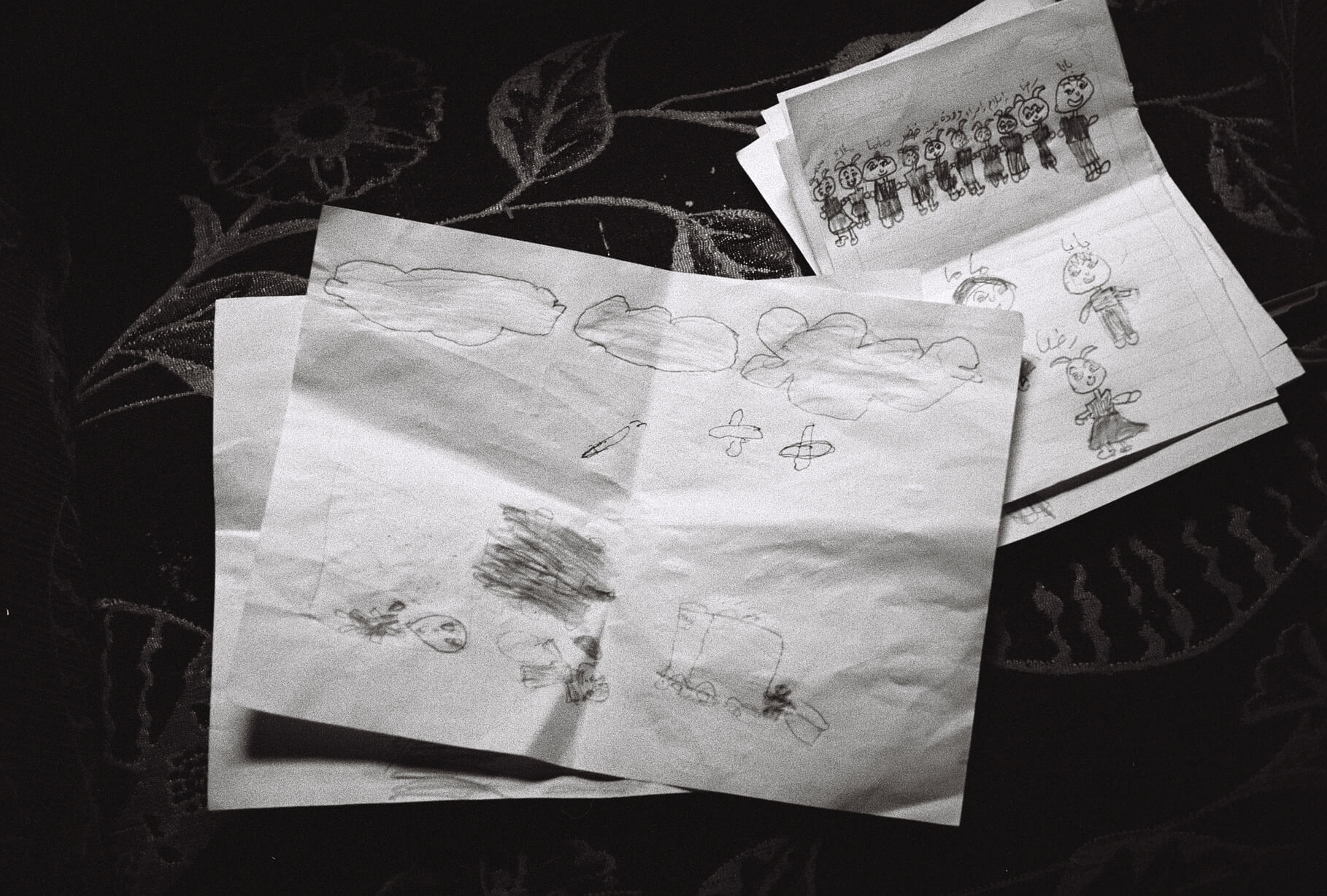

“I found she has constant nerves and had constant voices, thoughts and pictures coming to her in a very insistent way. I also conducted games and drawing sessions and I found she has a problem as she portrayed scenes of blood and the killing in these sessions. She used to have bad dreams and nightmares and often would wake up and go and stand behind the door, just waiting for her mother. She hears voices and has thoughts, like hallucinations. She would smell things that her mother used to do, like baking, but it doesn’t exist.

She keeps replaying a film in her mind of pictures of the incidents she went through, but she is not aware enough to collect the whole scene of what happened.”

Before we leave I witness one of Suha’s sessions with Islam and one of her surviving sisters Ruda. The pair are incredibly close. They have decorated a box with stickers of sunflowers and as part of Islam’s therapy; they are placing their mother’s possession in it.

“This is my mother’s scarf. She used to wear it when she went out.” Islam quietly speaks as as she places a red scarf in the box. Outside it’s starting to rain heavily, there is no electricity and the room has grown dark.

“My mother used to wear this blouse and now I am wearing it.” She places more objects gently in the box, “ this is my late sister’s Yasmin. These are pictures of my mother and two of my sisters.

“Islam,” Suha reassures, “you can keep this box with you all the time. Whenever you want to talk to your mother you can open it and take out the things that remind you of her, so your mother can always be around you. Islam, what would you like to say to your mother?

There is a pause before Islam answers. “I love you, I miss you, and please keep coming so we can remember you.”

Later I speak with Rawya Hamam, a psychiatric nurse and psychologist Dr Hasan Zeyada work at the Gaza Mental Health Community Project a charity that provides support across Gaza City.

“Its not just children with special needs,” Rawya explains, “In the war, around one third of those killed were children (561 children) and around 110,000 families were displaced from their homes. The basic psychological need for children in the whole world is to feel secure but in this war insecurity prevailed everywhere.

“Trauma affects children on so many levels – cognitive, emotional, physical. The most common symptoms were lack of concentration and attention – they can sit in class but they are just thinking all the time of the blood, the shelling… … I remember what my colleague said about the autistic children, you know because the autistic child needs routine, she said two autistic children made a suicide attempt because the very strong sounds from the shelling made them very terrified. So two autistic children entered the ICU in Al Shifa hospital because they tried to kill themselves“

Her words leave me cold. I think of the Autistic children I cared for, how loud noises would upset them. The sounds of the bombardment must have been intolerable for all those living here, but for those with greater sensitivity; unbearable.

“I see the question from a human rights perspective” interjects Hasan, “I think we can say that all the children in Gaza are specialized cases and they have need for special care. And you can imagine, for any child, just imagine the feeling of insecurity, the feeling of helplessness and powerlessness, and how you can see our children react. I think all children in Gaza have special needs.”

For some the war has also left a physical legacy. As a baby, Odai Ali, was struck by a fever that left him unable to hear and also affected his physical and intellectual development. He started at a sign language school, but he struggled and when he also started to get epileptic fits at 10 he had to leave.

Despite being unable to speak or sign, Odai developed his own way of communicating through hand gestures that his family have learnt to understand. After having to leave school, Odai found comfort in helping at the farm they owned. He especially enjoyed milking the cows.

All that changed on 10th July last year. Whilst Odai was giving water to some cows, the farm came under Israeli attack; unable to hear the jets, he didn’t run for cover. A rocket landed near him, throwing Odai five meters where he landed on his back. The impact left him paralysed.

Now in a wheelchair, what independence Odai had has gone. Living in a second floor apartment, he’s now dependent on his family to get him down the stairs. He’s too scared to visit the farm and is prone to mood swings.

We are sitting outside in the sun; Odai, his parents, brother and beloved grandmother Amna.

“He understands about Israel and the war and that they fight and he understands what happened to him, “says his father Abu Addullah, “he has some sign language: pointing with a finger means shooting; moving his hand like he is picking something up, or a crab means shelling. When he knows there are planes he feels afraid and he doesn’t want to come out of the home. If he refuses to go somewhere he makes a sign for shelling or planes..”

“Odai is a minister and we are his servants!” laughs Odai’s grandmother, “all the family love him and support him. All of them come with gifts for him. We don’t want him to be angry. A lot of the time he feels upset and aggressive and we don’t want him to be like this so we try anything to satisfy him.

Life without love is not good. You have to love your family, the people, because love is a great thing.”

We all nod in agreement.

As I get up to leave I ask what will Odai do now?

“Visit the neighbors.”

So I follow as Odai pushes his wheelchair down the alley from the garden to the road. It’s busy; horse drawn carts loaded with rubble pass in the street, uniformed children on their way to and from school, water leaking from a broken sewer, everywhere signs of the ongoing blockade. As Odai navigates the potholed street, everybody seems to stop to shake his hand, smile or say hello.

Odai’s father slaps me on the back. “Remember,” he smiles, “this is Gaza.”

We stop at a small shop where we have coffee and chat. Friends pop in to say hello. Odai holds court, laughing and signing to his father, surrounded by the love and support of his community.

On my final visit to Maryam and her family I finally see the photograph I’ve been looking for. As I sit talking to Farah, I notice Maryam is holding onto her fathers finger, gripping it tightly. I pick up my camera, take a few frames and place it back down.

This trip has made me painfully aware of the restrictions my photography brings. I can never truly express the horrors of some people’s experiences, I’m not sure I even want to try. But strangely spending time with people, listening to them, observing with my camera has shown me something else.

It’s trite for me to say I see love or hope in such a situation. The realities for Maryam and her family are desperate and their outlook bleak. Maryam herself lives trapped in a nightmare, with little support. What I did see however was a moment of our shared humanity, a simple gesture that is universal and without barriers. A daughter who is looking for security, holding onto the hand of her father, who just wants to protect her. That surely should be a universal right.

OTHER STORIES