The Friendship Salon

June 2020

“We have a saying here, a community brings up a child, not an individual.”

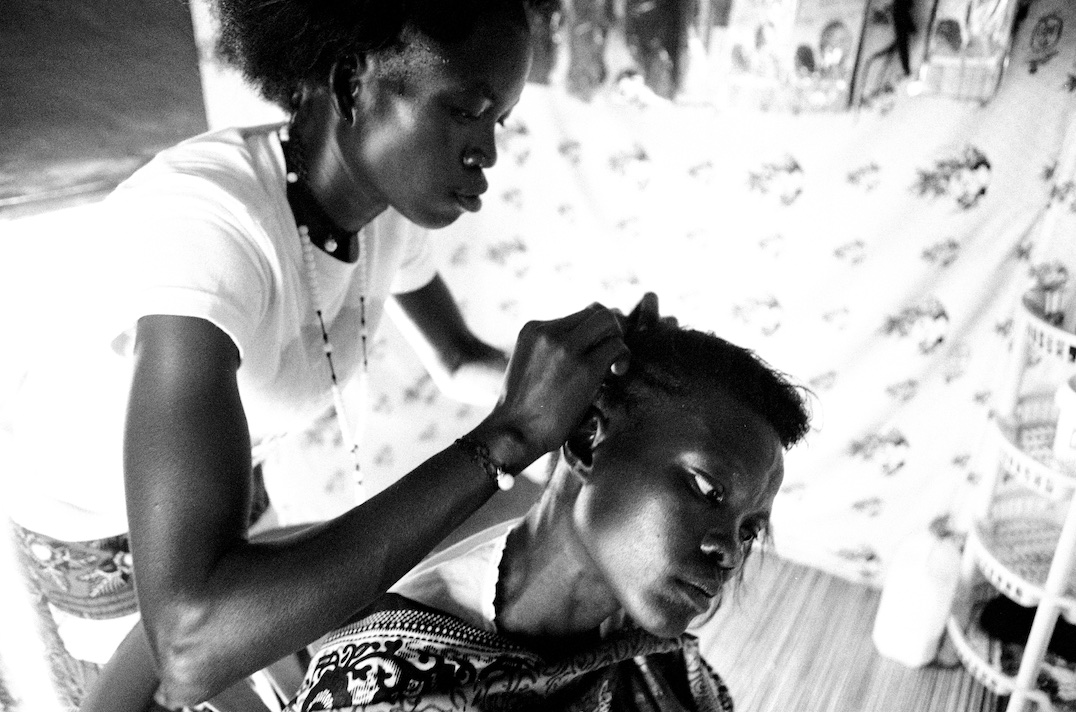

When Sarah Aba talks of home she remembers afternoons with her friends, taking a break from work to braid each other’s hair.

“It was a time when we laughed and gave each other advice,” she recalls wistfully. “Now I don’t know where any of them are.”

The world’s newest country, South Sudan, was marred by violence and instability long before its creation in 2011. Civil war then began in 2013 with both sides targeting civilians. This new instability worsened the impact of famine and led to the displacement of nearly four million people, two million of whom have sought safety as refugees in neighbouring countries. About 80 per cent of the displaced are women and children. They are particularly vulnerable.

This huge displacement has led to a fracturing of communities and families. South Sudanese grow up belonging to a tight network of family, extended family, village, clan, tribe; these connections and loyalties are from birth. So for those who find themselves alone, often for the first time, building new friendships and community can be a major challenge. Young mothers in particular often find themselves isolated in the new surroundings of a refugee camp. This has triggered an increasing suicide rate among young women.

“Everybody I know, I knew from the moment I was born,” explains Sarah as she tells me about the depression she felt on arriving alone in Bidi Bidi refugee camp in Uganda. At home most tasks, including bringing up children, are done communally. With nobody she knew around her, she found herself struggling.

As one UNHCR staff member said: “Loneliness is the greatest killer for South Sudanese refugees”.

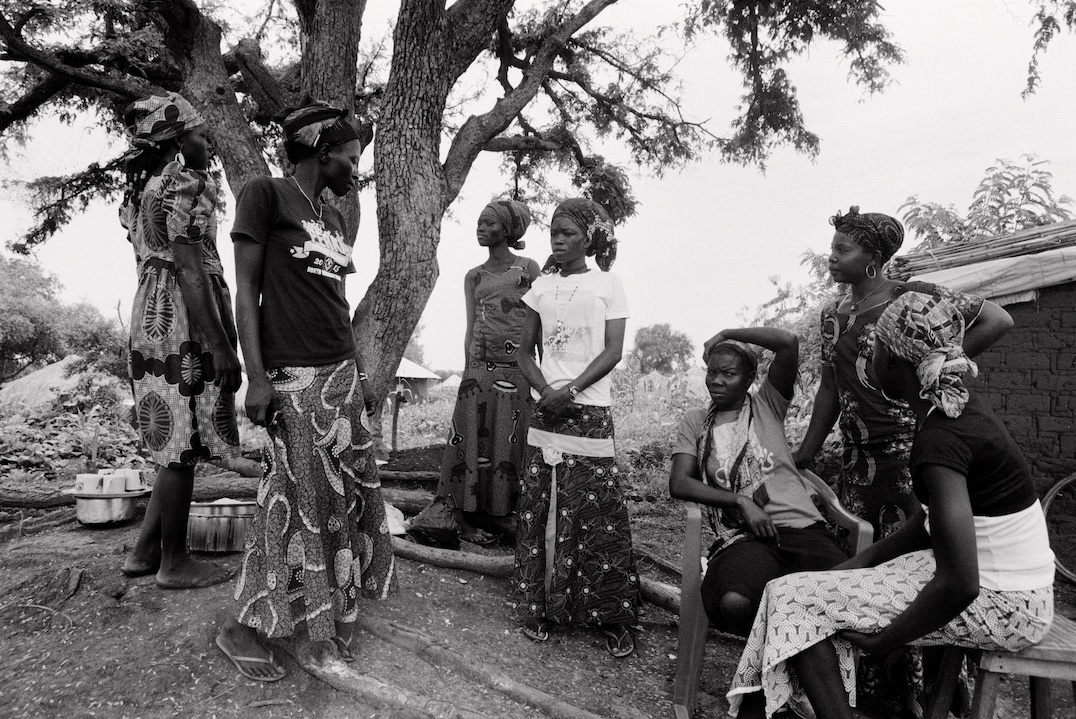

This is why Sarah and seven other South Sudanese refuges decided to do something about it. Despite having no training, they decided to set up a hair salon in Bidi Bidi refugee camp.

The camp, in northern Uganda, near the town of Yumbe is the second largest refugee camp in the world, where nearly quarter of a million South Sudanese live, the majority since 2016. It is in reality a small city and with the support of the Ugandan government, UNHCR and other agencies many small businesses have been set up.

For the women who run the salon it is so much more than a business. They wanted to build their own community for single mothers. It keeps them busy, stopping them from spending time alone thinking on what has happened. Many have lost family members, husbands, children. They were also creating a place where they could support each other and build their own family.

“It’s difficult for women to talk and tell stories,” explains Sarah, who is something of a mother to the group. “In the salon, when something is wrong, we can tell and so we ask, we talk and together we find answers”

Celina Amana, another of the cooperative, agrees: “when I arrived, I had a small child, was pregnant, my husband had disappeared, I was so alone. But being together you find solace in each other’s stories.”

But the women also see the salon as a business, they are all committed to making it a success and what small money it brings in goes to supporting their children.

“Why do you think we make so much effort into looking this good? If somebody sees us, they say ‘I want to look that good’ so they ask where I got my hair done and they come here. We are walking adverts for the salon!”

But for some there is another reason why the way they look is important. South Sudan has seen an upsurge in sexual violence in recent years. Women, who are often fleeing alone with their young children, are regularly targeted by the various fractions. Even in the camps, women living alone are often victims of sexual and gender-based violence.

“Many women here are scared and hide themselves,” explains Yeno Lili, “but we are proud to look good, to stand out and be seen as women. Why should we hide? Together we feel safer.”

The salon itself is based in a small hut made of plastic sheeting and canvas. It has no electricity or equipment. In fact, the women, who have trained themselves, have to work with the most basic of equipment; a couple of combs, a brush, some scissors and a mirror. But that hasn’t stopped the salon becoming a huge success. More than that, it has become a community.

“In South Sudan I had a big extended family,” says Mary Sande, “I knew everyone in the village, but when I arrived here, I was alone. My husband left, I had two children. There was nobody to advise me, to turn to for support. I thought about things too much. Then I found this group, the salon. They are my family.”

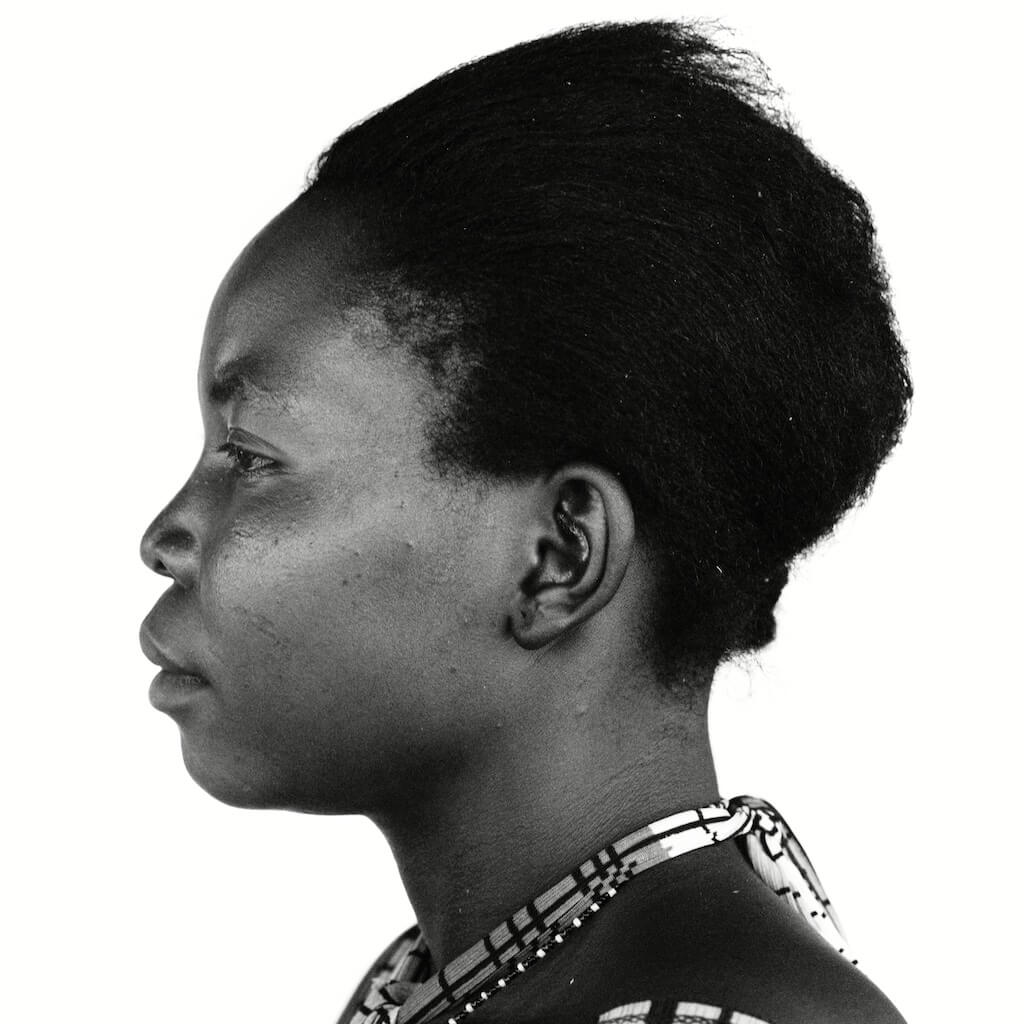

Mary Sande 20 years old Arrived at Bidi Bidi in 2016

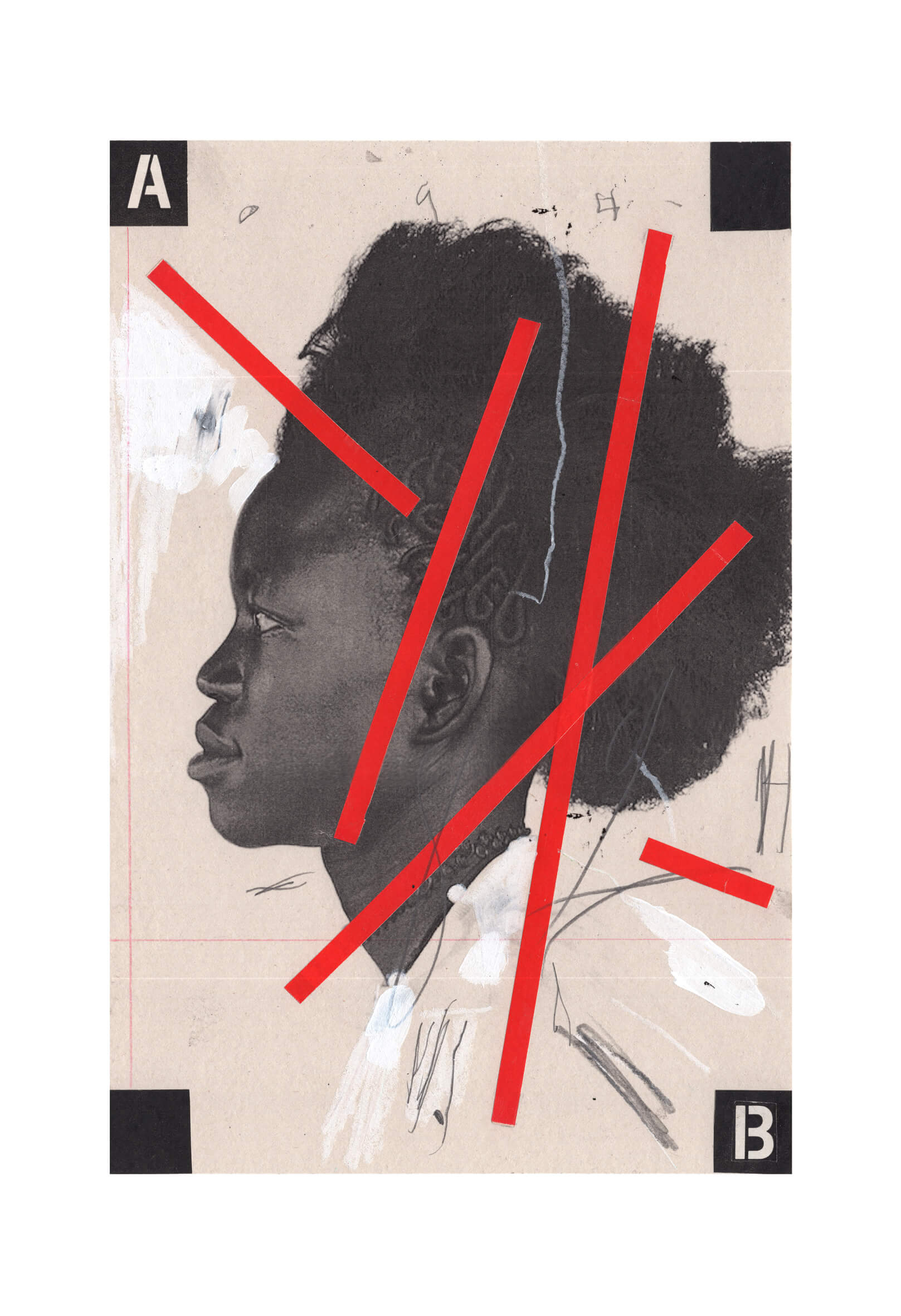

The Stamina – Stamina is a title of a song that brought Ugandan singer Eddy Kenzo to fame. But it was the dancer in his music video, Ronnie, whose moves wowed the nation. His hairstyle was iconic and it was quickly being copied in saloons across the region under the name – the Stamina (for his relentless energy).

Yeno Lili 24 years old Arrived at Bidi Bidi in 2016

The Banda Inje – which means, “husband don’t think about marrying another woman”

Khemisa Mary 26 years old Arrived at Bidi Bidi in 2016

The Macron Pencil or Dududu (caterpillar)

Celina Amana 25 years old Arrived at Bidi Bidi in 2016

Banda Pembeni – which means, “better put that other partner aside”

Ariye Margret 20 years old Arrived at Bidi Bidi in 2016

The Stamina – Stamina is a title of a song that brought Ugandan singer Eddy Kenzo to fame. But it was the dancer in his music video, Ronnie, whose moves wowed the nation. His hairstyle was iconic and it was quickly being copied in saloons across the region under the name – the Stamina (for his relentless energy).

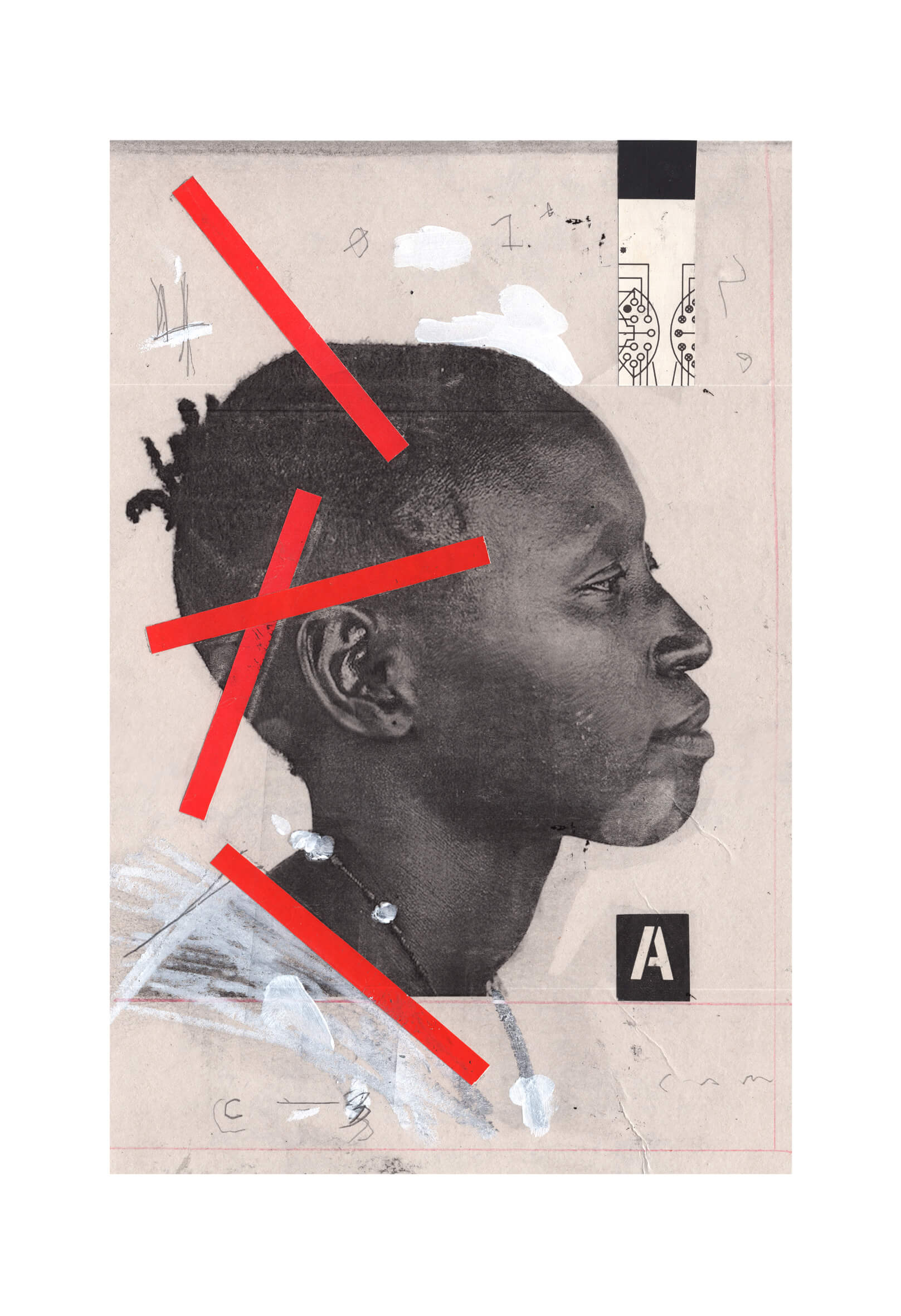

Sarah Aba 25 years old Arrived at Bidi Bidi in 2016

Growing out hair ready to create new style

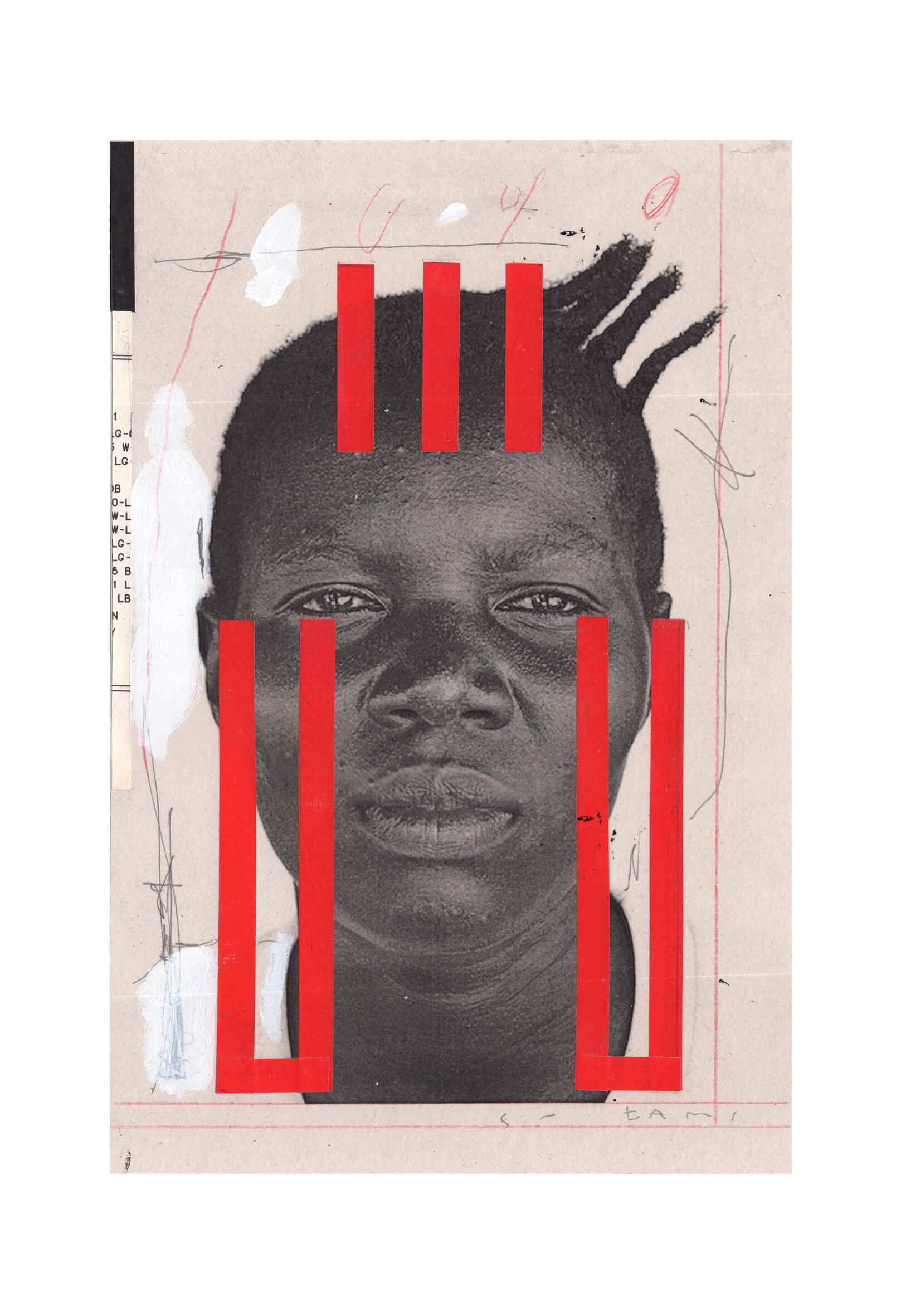

Susan Mordn 23 years old Arrived at Bidi Bidi in 2016

The Kura/Unity – “when all the tribes of South Sudan come together like the braids of hair, we will have peace”

The portrait session was designed by the members of the salon, who wanted to highlight the various styles they had created. A set of prints was sent to the women for their use.

Thanks to Yonna Tukundane for his support.

This story was done in partnership with UNHCR

OTHER STORIES